The "glorious fifty"

by Hatim Madani

Astronomy has been propelled by this new millennium and its digital revolution in which information technologies play a key role in the popularization of the discipline.

Never before in its history, was this science put within the reach of all, with so many differing ways to insure its dissemination. Nowadays, within the framework of the participatory science, it is possible for everyone to be able to contribute significantly to astronomical research. Personal telescopes are now more affordable than ever and amateur astronomer communities have grown substantially worldwide.

Space exploration has recorded huge achievements over past decades and our vision of the solar system and the Cosmos as a whole, has been completely modified. The discoveries of new exoplanets are opening a fascinating era for the search for extraterrestrial life.

The super giant telescopes new generation is underway with the construction of the three Cyclopes EELT, TMT and GMT supported by the James Webb Space Telescope.

I have bought few month ago an old astronomy book, a French edition of "The Universe" -Time Life Nature Library, published in 1962, perfectly preserved with a wonderful picture of Andromeda Galaxy in the book cover. I own many astronomy’s books and magazines of the 60s and 70s in my personal library but this one had a profound effect on me, may be because it seemed brand new.

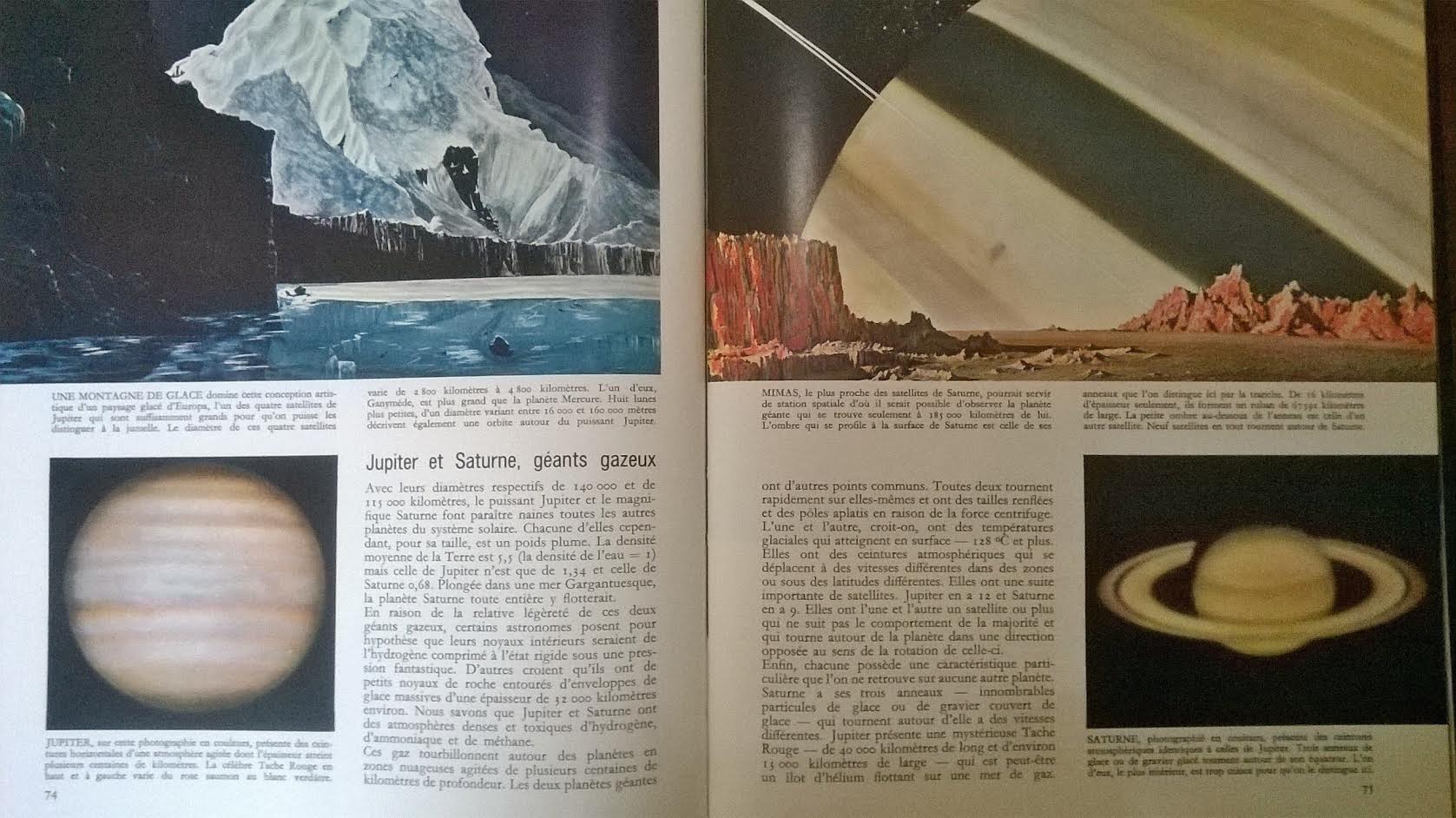

Reading this book take you back to an exciting time in which astronomy seemed as a secretive science, a discipline of specialists and privileged amateurs. The book invites any curious reader to know more about astronomy, offering beautiful colored images and detailed information about the subject.

It was interesting to make the comparison between current and older data presented in the book and update them in the light of current discoveries.

In the chapter regarding astronomical instruments, the Hale telescope in the Palomar Observatory with his 5 meter mirror and 500 tons was the biggest giant.

The pictures of planets published were the best available at that time and are indeed wonderful despite their lower quality. Jupiter and Saturn seem mysterious, and patiently wait for Pioneer and Voyager probes for unveiling their beauty.

The Orion nebula is presented as a stellar nursery but it was yet difficult to be able to penetrate down the deepest gas layers.

Galaxies remain indiscernible in the deep space and super massive black holes theories haven't been yet clarified.

In conclusion, some questions are put:

Is the universe really expanding?

What are the dimensions of the Cosmos?

Will man find answers? This question was in reference to the discovery of a strange galaxy, Centuras A, emitting a large amount of radio radiations.

The book ends with a statement that mirror’s dimensions limits had been reached and the use of stratospheric balloon to avoid disturbances of the atmosphere could be envisaged.

It is quite unbelievable that such a huge leap forward has been achieved in astronomy over half a century. Those glorious fifty years remain a pivotal period in astronomy history, undertaken by a generation of brilliant astronomers.

Today, astronomy is living its golden age, and I think we all appreciate being the privileged witnesses of this fabulous epoch.

Hatim Madani is a Master graduate in international business and works in private sector. he was involved in the astronomy field trough amateur astronomers clubs. During IYA 2009, he worked in partnership with the National Commission of UNESCO to launch Aldebaran project( project for creation of schools astronomy clubs in the country) - /UNAWE Morroco Coordinator/

Hatim Madani is a Master graduate in international business and works in private sector. he was involved in the astronomy field trough amateur astronomers clubs. During IYA 2009, he worked in partnership with the National Commission of UNESCO to launch Aldebaran project( project for creation of schools astronomy clubs in the country) - /UNAWE Morroco Coordinator/

Astronomers Without Borders Coordinator.

Wondering about the Universe

By Reina Reyes

"The most incomprehensible thing about the Universe is that it is comprehensible." Albert Einstein

How do we comprehend the Universe? How are astronomers and astrophysicists able to study its myriad of mysteries? Dark stars so dense that even light cannot escape. Explosions so energetic they outshine the whole galaxy. Tiny planets orbiting around double stars as in science fiction films. We humans have explored far beyond our earthly shores, and there is no end in sight.

We speak about "The Great Silence"-- it seems that no one is communicating with us from outer space-- but the truth is, the Universe is sending us messages, night and day. Astronomers have found ways to listen, to the light waves, radio waves, X-rays, cosmic rays, neutrinos, and most recently, gravitational waves, coming our way.

Our detectors welcome them warmly after what could be millions, or even billions, of light years traveled across the dark, empty expanse of space. We carefully record each precious photon, and put together a picture of where it came from, and how it came to make its way to us. Piece by piece-- diligently, playfully, cleverly, we rebuild the Universe.

With our telescopes, we participate in this Universe-listening and Universe-building endeavor. Observational astronomers specialize in capturing subtle messages from the skies and exploiting them for insights about the workings of Nature. Meanwhile, theoretical astrophysicists exploit the laws of Nature to create models to better understand and explain what we observe.

Together, theorists and observers weave a beautifully complex yet elegant understanding of astronomical phenomena, however strange and spectacular they may be. The Universe is full of mystery and wonder, but is also orderly and comprehensible, as Einstein marveled.

One can look up to the sky in awe, mouth agape, yet at the same time, listen with concentration-- telescope and computer in tow, brows furrowed and minds aglow. The Universe will speak to whoever will listen. Her invitation is wide open-- and up to us to take.

Where do we begin?

For countries like mine-- the Philippines-- that have only recently made nascent progress towards developing our national space science, technology, and industry, the question remains if we are ready to accept this cosmic invitation.

If we heed the call, we will have the unique opportunity to inspire the next generation of aspiring scientists, engineers, technologists, and technopreneurs-- and give them the opportunity to explore the wonders of the Universe and utilize the gifts she has to offer.

We have already taken the first steps on this long and challenging, yet ultimately fulfilling, journey to space. The first microsatellite of the Philippine Scientific Earth Observation Microsatellite Program, PHL-Microsat-1, was successfully launched in March last year. It was a flagship project of the national Department of Science and Technology (DOST) and the University of the Philippines, in partnership with Hokkaido University and Tohoku University of Japan. The satellite is also called Diwata-1, after a fairy-like deity in Philippine mythology. The second satellite, Diwata-2, is currently under development and scheduled to be launched next year.

In parallel, initiatives to establish a Space Research and Development Agenda to set forth space-based capabilities, including policy and research and development infrastructures, are gaining momentum-- with the ultimate objective of the establishment of our own national Space Agency. It is a promising sign to see these efforts pushed by the younger generation, with visionary leadership from my colleague and friend, Dr. Rogel Mari “Romar” Sese, as head of the DOST-funded National Space Development Program.

There is a long way to go, but also so much to look forward—and upward—to. So, as we have always said: Per aspera ad astra!

Reina Reyes, Ph.D. is a data scientist and lecturer at Ateneo de Manila University and Rizal Technological University in Manila, Philippines. She obtained her doctorate degree in Astrophysics from Princeton University. For more, you may visit her webpage at: www.reinareyes.com.

Reina Reyes, Ph.D. is a data scientist and lecturer at Ateneo de Manila University and Rizal Technological University in Manila, Philippines. She obtained her doctorate degree in Astrophysics from Princeton University. For more, you may visit her webpage at: www.reinareyes.com.

Attribution Note: A slightly-different version of this article has been published in the Philippine Panorama on February 26, 2017.

The Celestial Experience

By Monica Young

“Wow, the Moon is so big!”

I’ve invited friends over to see the so-called supermoon. I know that this particular full Moon isn’t noticeably bigger than any other month, but why not take advantage of the hype? I now have two five-year-olds, a two-year-old, and even a one-year-old out in the dark, all of them vying for turns at my telescope.

The hands-on experience is a far cry from my graduate school days, many of which were spent at a computer analyzing thousands of X-ray sources and examining their spectra. I pored over images from the XMM-Newton telescope, in which 58 gold-plated mirrors nestle inside each other like layers of an onion, each one doing its part to focus incoming X-rays. The photons the spacecraft captured told stories of an exotic universe.

In the sources I studied, a precious few X-rays had made their way to Earth from the hot, innermost regions of the gas disks around supermassive black holes — the last glow of material falling into the gravitational pit. For each source, I arranged those photons into a spectrum. A single spectrum of a faraway active galactic nucleus is like a cipher; it reveals very little about its source. But if you collect thousands of such spectra, they begin to tell a story about the relationship between the gas that feeds a black hole and the gas that escapes.

During graduate school, I mastered radiative processes and learned how quantum effects could reveal themselves in spectral lines. But I didn’t know the constellations. In fact, I struggled to learn the basic patterns of the stars on the fly, as I taught them during night labs to intro-level astronomy students. If I had ever told the students that I knew only a little more than them, they would have been surprised — surely an astronomer would have to know the stars?

Yet gazing up at the sky, while still very much in practice among the pros, seems to be a lesser part of the field’s future. As ever-bigger telescopes scan the sky and collect petabytes of data across the electromagnetic spectrum, the experience of professional astronomy has become more a matter of data analysis than data collection.

Is that a bad thing? Walt Whitman may think so, but I don’t. My favorite part of astronomy — and the part I miss the most now that I no longer do research for a living — was the analysis: that moment when the data begin to take shape and tell a visual story of the physics responsible for far-off happenings.

Still, as I stand shivering in the “mystical moist night-air” and talk with my kids and their friends about what they see on the Moon, their excitement is contagious. “It has lots of circles!” they cry, as they glimpse for the first time the craters that dot the lunar surface. Though I’m sure not going to get any “perfect silence” tonight, it’s nevertheless a good time for me to experience the sky with new eyes.

Dr. Monica Young earned her Ph.D. researching the behavior of supermassive black holes in distant galaxies. In 2012, she joined the talented team at Sky & Telescope, where as Web Editor, she edits, writes, and commissions web news stories and magazine feature articles.

Dr. Monica Young earned her Ph.D. researching the behavior of supermassive black holes in distant galaxies. In 2012, she joined the talented team at Sky & Telescope, where as Web Editor, she edits, writes, and commissions web news stories and magazine feature articles.

On the Persian New Year and Being Human

By Mike Simmons

With the recent passing of the March equinox, those in Earth’s northern hemisphere look forward to spring. The season represents a new cycle of life, and a time to focus on the things that make our lives special. Across the lands of the former Persian Empire, the moment the Sun crosses the celestial equator marks the beginning of a new year on the Persian calendar, and the start of the ancient celebration of Nowrouz. With up to 13 days of celebration, Nowrouz is like an amalgam of several US holidays: New Year, Christmas, Chanukah, Thanksgiving, and more rolled into one.

Modeling the Phases of the Moon Activity

April 6

With the Modelling the Phases of the Moon activity by Noreen Grice, from You Can Do Astronomy LLC, we intend to simulate the phases of the Moon. Using low-cost materials, supported by how-to guidelines for the activity, you can help students visualise the cycle.