By David A. Hardy, FBIS, FIAAA

- Published: Tuesday, May 20 2014 23:56

Title: Ocean of Space by David A. Hardy (acrylics on canvas; from the private collection of M.C.Turner)

Caption: Here we see the earthlike planet of a star far beyond our own Milky Way. Above its ocean the sky is dominated by the great pinwheel of another spiral galaxy, and while the mountains are lit by a setting reddish star, a blue companion is rising on the horizon.

When discussing astronomical art it is important to understand what it is – and is not. For instance, it is not science fiction; although there is an overlap, science fiction depends much more upon the imagination than on science fact. The term ‘space art’ is also sometimes used to describe this genre; there is no real difference, except that the latter term usually encompasses art that includes hardware (spacecraft, bases, rovers and other vehicles) and figures such as astronauts, while ‘astronomical art’ is more likely to depict purely landscapes and/or objects in space, such as planets, moons, stars, galaxies, nebulae, etc. Most (though of course, not all – there are a very few exceptions!) artists who produce this type of work are members of the International Association of Astronomical Artists (IAAA).

Not all of these are realists, and some produce work which is impressionistic, expressionistic, abstract, symbolic or surreal; as I said in my last article, most of the Russian artists who attended our workshops in 1988 and 1999 come into this category, but others, like cosmonaut Alexei Leonov and Andrei Sokolov, paint in a realistic style. The majority have backgrounds which enable them to interpret accurately the data from observatories and space probes, and convert them into believable scenes. Although the fact is not always appreciated by the public in general, this work is, and always has been, essential because it forms a link between the often abstruse and incomprehensible data, theories and symbols of scientists and the wider world beyond the walls of their laboratories or observatories. Indeed, it is an interesting reflection upon the workings of modern science that scientists and astrophysicists often seem unable to visualize the appearance of the objects or fields of research in which they are involved, and are amazed when they see how an artist is able to interpret it visually. Yet it is only through such visualizations and reconstructions that the public is able to understand what is being discovered “out there.”

Title: Neighbours by David A. Hardy (acrylics on canvas)

Caption: This is an example of a ‘symbolic’ work. It shows the Earth, Mars and Moon to scale, with their appearance from space on the right, and a ‘typical’ landscape on the left. In space behind them is the Milky Way galaxy, and beyond that the neighboring Andromeda Galaxy or M31.

My own work generally comes into the realistic category, though I have produced quite a few “symbolic” pieces, as shown here. When I started producing space art in the early 1950s I used watercolor, it being the only medium I knew. In this, the only white is normally the paper, so it requires care.... But for astronomical subjects, with their often black skies and strong contrasts of light and shade, it was far from ideal. I discovered Indian Ink, and then colored inks, and for a while used these. Then I came across poster colors, including white, which were much more satisfactory. Finally, after attending an Art class, I settled on gouache, with which glowing, transparent watercolor techniques may be used, but much stronger effects may be achieved and the use of white is allowed (essential for painting stars on a black background!). In 1957 I got my first airbrush, which was ideal for painting the glow around stars, galaxies and nebulae, and atmospheres, and saved a lot of time. I used gouache until the 1970s, when science invented polymer and then acrylic media. These are not only waterproof when dry, but allow effects similar to oils, such as “impasto” – applying a thick texture with a palette knife. And of course they dry much more quickly than oils, which can take days or even weeks. Chesley Bonestell never used an airbrush, preferring very tight oil techniques such as stippling; however, perhaps as a result of his work as a matte artist on movies, he was not averse to working over photographs of model landscapes.

Title: Time and Space by David A. Hardy (acrylics on board)

Caption: Another symbolic painting. On the left is the ancient ‘observatory’ of Stonehenge, merging with a futuristic city and observatory, while in the sky is the timeless phenomenon of a solar eclipse.

I too have always been open to experimenting with new methods, and in the 1980s I used photography to complement my art, doing my own developing, printing and darkroom work, which included “derivative” techniques, such as making composites of several images, distorting them, using high-contrast films or even “line” effects. I used infra-red film, both monochrome and color, to produce special effects. Of course, most of these required working in a tiny darkroom (mine was a cloakroom under the stairs) at a temperature of 18oC, in a red light or even total darkness; so when I learned about the new personal computers which were becoming affordable, I quickly purchased one. In 1986 I got an Atari ST 520 – with 512k (yes, K) of RAM. Within years I moved up to an ST 1040, and finally a Falcon, but even here I could only use 16 colors, or 32 with interpolation. I managed to produce some publishable art, but it wasn’t really satisfactory, and my wife suspected me of merely playing with “boys’ toys”. So in 1991 I invested in a Power Mac, with 512MB of RAM, something I have never regretted, as I have used Macs and Apple products ever since.

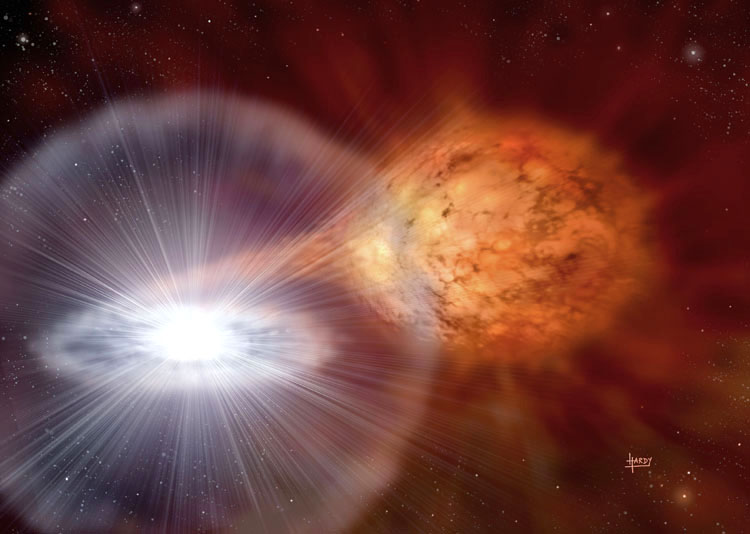

Title: RS Ophiuchi by David A. Hardy (digital; Photoshop)

Caption: This image was commissioned by PPARC for use as a press release to announce the observation in 2006 of the explosion of a recurrent nova produced by a white dwarf and a red giant star, circling each other in a close orbit. It also appeared as an Astronomy Picture of the Day.

I got Photoshop immediately, with a number of filters and plug-ins, and I was soon able to produce images that were of good enough quality to be reproduced in books and magazines, such as Astronomy and Sky and Telescope. Later the advent of the Internet allowed me to send images as jpegs by e-mail – so much better and quicker than having to entrust painted art on board to the tender mercies of the Post Office. Nowadays many artists work purely digitally, some of them using 3D programs such as Vue d’Esprit or Lightwave. These enable the production of “models” which can be moved in three dimensions to any position, given textures, lit, reflections and shadows added, and so on. This enables highly realistic, even photographic results to be produced; but to some people these images can appear rather bland and soulless, lacking individuality. Certainly it can be difficult, just by looking at them, to know who the artist was; but there are some artists, such as astronomer Dr. Dan Durda, who place their own stamp on their work. Personally, I sometimes use Poser to create figures, and have used Terragen to generate landscapes; but I try to ensure that my work is still recognizable as my own. Generally, I use only Photoshop to “‘paint” by moving around pixels instead of pigment. But I still enjoy painting a large canvas, and using impasto (which cannot be done digitally!) for commissions etc.

David A. Hardy is European Vice President of the International Association of Astronomical Artists (IAAA). The IAAA’s website is “www.iaaa.org.”

ITitle: Comet Lander by David A. Hardy (digital; from Futures: 50 Years in Space by David A. Hardy & Sir Patrick Moore, 2004)

Caption: This was produced using a terrain generated in the original version of Terragen, then finished in Photoshop. It shows a hypothetical lander, eclipsing the Sun, touching down onto the surface of an active comet which is emitting plumes of gas and dust.

- Will photo libraries please note that all of my images on this site are provided by myself and are used with my permission, as a member of AWB. (They are NOT to be used for any other purpose without written permission.)

David A. Hardy

David A. Hardy

Comments