Report

by Adrian Fartade, Italy

- Published: Tuesday, May 14 2013 09:33

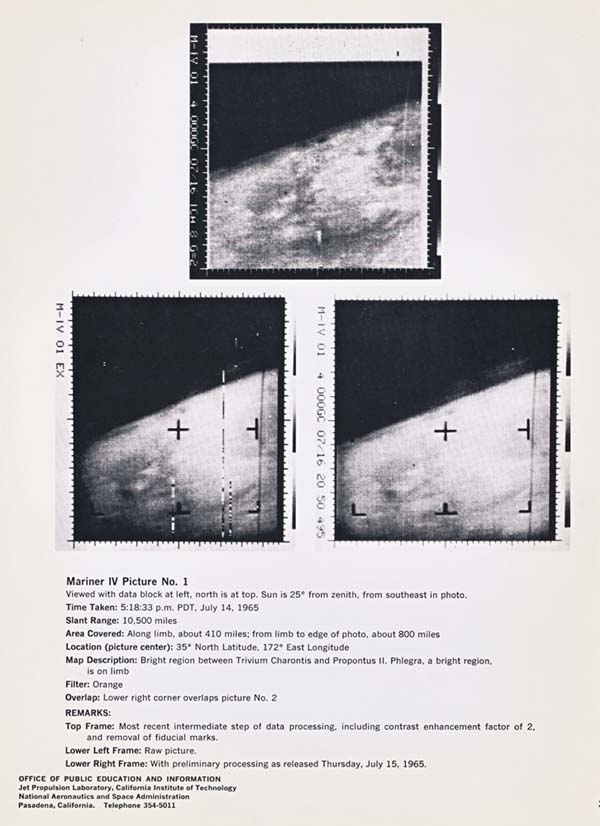

In late 1964, two missions were launched by NASA with destination Mars! They were Mariner 3 and Mariner 4. Both of them were sent to flyby the Red Planet and take the first pictures and scientific observations, transmitting to Earth precious information about interplanetary space and Mars. At that point in history no one had ever seen how Mars looked like. There was a lot of speculation and with earth telescopes it was possible to see that Mars had an atmosphere and changes in color and many so dark patterns forming seasonally. So there was a hope in many that maybe, just maybe, we could see signs of vegetation on the surface, and life! So when these to missions were sent, there was an incredible historical feel to it. Everyone was very excited to see the first glimpses of Mars!

Unfortunately the shroud encasing the first spacecraft atop its rocket failed to open properly, and Mariner 3 did not get to Mars. Unable to collect the Sun's energy for power from its solar panels, the probe soon died when its batteries ran out and is now derelict in a solar orbit. But Mariner 4 did make it to Mars, and between July 14 and July 15, 1965, it transmitted the first ever direct data from Mars.

The spacecraft took a total of 21 picture with the different filters it had (green and red). The pictures were saved on tape and then the probe went on behind the planet and the signal was lost for a few hours. Just imagine being one of the scientists or engineers at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, waiting there impatiently, listening to the static noise from Mariner 4, unable to know what was going on or if you would ever hear from it again. Remember, the team did not yet have any of the pictures.

The flyby started at 00:18:36 UT, and minutes after the probe ended behind Mars. At 03:13:04 UT, the signal was reacquired and all systems were nominal! Cruise mode was re-established and the transmission of images started about 8.5 hours later. This lasted until 3 August. The engineers were very anxious about the photos because there were some error signals that pointed towards problems with the tape recorder, that by the way, was a spare and not the original intended for use (it had to be used after the failure of the Mariner 3 probe.) Richard "Dick" Grumm oversaw the tape recorder and its use, and decided to try and take the most of it anyway.

The flyby started at 00:18:36 UT, and minutes after the probe ended behind Mars. At 03:13:04 UT, the signal was reacquired and all systems were nominal! Cruise mode was re-established and the transmission of images started about 8.5 hours later. This lasted until 3 August. The engineers were very anxious about the photos because there were some error signals that pointed towards problems with the tape recorder, that by the way, was a spare and not the original intended for use (it had to be used after the failure of the Mariner 3 probe.) Richard "Dick" Grumm oversaw the tape recorder and its use, and decided to try and take the most of it anyway.

So, here we are at JPL, in the morning night, after no sleep, and data is finally returning from space! But we're still talking about 1965 computers here! It took hours for them to process the data into a real image. So while they were waiting for the data to be crunched, engineers thought of different ways of taking the 1's and 0's from the data and creating the image by hand.

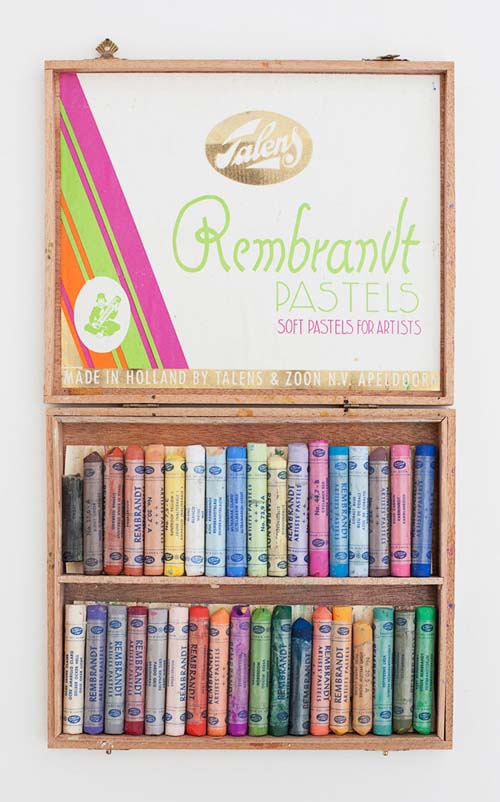

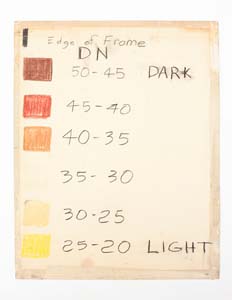

They tried a few tricks but nothing seemed to work until they found that to most efficient way was to print out the digits and then color over them with chalk of various variations of gray, based upon how bright each pixel was meant to be. But... there was no gray chalk at JPL, so Grumm had to run out that morning and find an art store. He asked for some chalk of different shades of gray, but the art store seller replied that they did not sell chalk! But what they did have was a set of colored pastels. Richard didn't want to spent too much time there, away from the data streaming back from Mars, so he bought the pastels and ran back where he had 1's and 0's printed out on a ticker tape about 7.6 cm long, and his team colored them by their brightness level.

Funny thing is that the color scheme chosen, with brown and red, was not chosen because of the "Red" Planet, but simply because Grumm was trying to find a scheme equivalent to the grey scale. In that age, no one knew what the real color of mars would be. It's funny how he got the colors just about right anyway, by pure chance. He tried some other schemes too, like green and purple, but finally decided to use brown/red!

Here's a side story from Dan Goods, from JPL, who was there that day: "while he (Grumm) and his team were coloring the image, the JPL PR folks were getting nervous that the news media would see this thing and not the “actual” pretty image. They told them to quit, but Grumm argued that this was being done to confirm whether their instrument was working or not. So they allowed him to continue if he did it behind a movable partition wall with armed guards around them! Eventually the media found out about it and got so excited the PR people couldn’t keep them out. So it became the first close-up image of mars to be seen on tv."

Here's a side story from Dan Goods, from JPL, who was there that day: "while he (Grumm) and his team were coloring the image, the JPL PR folks were getting nervous that the news media would see this thing and not the “actual” pretty image. They told them to quit, but Grumm argued that this was being done to confirm whether their instrument was working or not. So they allowed him to continue if he did it behind a movable partition wall with armed guards around them! Eventually the media found out about it and got so excited the PR people couldn’t keep them out. So it became the first close-up image of mars to be seen on tv."

The first image colored was an image of the limb, or edge of the planet. If you look closely you can see there is only dark brown at the bottom. It's because that's space! The light area above is part of the planet, and the orange between are the first clouds seen above Mars!

The total data returned by the mission was 5.2 million bits (about 634 kB). All instruments operated successfully with the exception of a part of the ionization chamber, namely the Geiger-Müller tube, which failed in February 1965. In addition, the plasma probe had its performance degraded by a resistor failure on December 8, 1964, but experimenters were able to recalibrate the instrument and still interpret the data.

The images returned showed a world with vast craters, and the Mariner 4 instruments found an atmospheric pressure of 4.1 to 7.0 milibars, with temperatures of -100°C and no magnetic field and no radiation belts. So, Mars was far beyond being a world with strange life forms. It seemed to be a barren cold desert and a dead planet.

But not all hope was lost. Many said that if you took similar photos of Earth, you would not find sings of life, so with 22 small pictures you couldn't just yet say if there was life or not. The mission was a big success and it is still one of the landmarks in the history of our exploration of the solar system! Talking about the picture, when they finally finished the piece they literally took a saw to the movable wall and cut it out, framed it, and gave it to the William Pickering, the JPL director at the time.

Images credit: NASA/JPL

###

Graduat student in history and philosophy, at the University of Siena, Italy, Adrian Fartade, age 26, is specialized in the history of science, astronomy and space exploration. He also works as a theatre actor and writer, and is now majoring in anthropology at the University of Siena. Editor of the science blog Link2Universe, he uses theatrical languages and skills to better outreach science and astronomy to the public of all ages and preparation.

Graduat student in history and philosophy, at the University of Siena, Italy, Adrian Fartade, age 26, is specialized in the history of science, astronomy and space exploration. He also works as a theatre actor and writer, and is now majoring in anthropology at the University of Siena. Editor of the science blog Link2Universe, he uses theatrical languages and skills to better outreach science and astronomy to the public of all ages and preparation.

Comments