- Published: Monday, September 21 2015 14:40

AstroArts – September 2015 Post #3 In this post (#3 of 4) I’ll talk a bit more about the logistics of setting up the recording session, and some of the technical production of making a live, on-location recording...

In September 2014, Nik and I attended a housewarming party where the hostess (an artist) encouraged the guests to contribute their art, so I showed up with a quiver of my favorite flutes. After playing for a while, I re-joined the table where my husband was chatting with other guests. I mentioned having been inspired many years ago by hearing jazz flutist Paul Horn’s recording Inside the Taj Mahal, and wanting to do a similar album. Nik, always my biggest supporter, promoted the idea that Native American flutes played inside a telescope dome would be a natural pairing of sound and science. One of the guests was Phil Mantione, who introduced himself as audio engineering instructor and said he was very interested in this project. Much to my surprise and delight he offered to take the lead in doing the recording. Nik decided that now was a good time to make the official request to the observatory director for a formal recording session, so we put the wheels into motion...

The first step was to choose a dome, and get official permission to use it. On September 19th I drove up to the observatory with about eight flutes and my Sony digital recorder, to do some audio testing after the evening’s observing session was over. While the acoustics in the 60-inch dome were interesting, the 100-inch dome was spectacular, and I spent about 15 minutes playing various flutes, in different locations inside the dome. Tom Menegheni pointed out a specific spot directly underneath the telescope base, where the echo was dramatic. Leaving my Sony recorder on a chair, I walked about 20 feet to the center of the “bullring” and played an improvisation that I later named Lullaby for a Lost Child. This tune, which was the last thing I played for my test session, wound up being the track I converted to MP3 and accompanied my request to use the facility for my album. People loved the track, were incredibly supportive and complimentary about the idea, and permission was granted. I would need to hold my recording session at night (after the visitor gallery & park grounds were closed to the public), on a night when the telescope would not be booked for viewing, and under favorable weather conditions (it was now autumn, and the chance of rain & snow after a hot, dry summer was increasing).

In the meantime, Phil was busy gathering a recording crew and equipment from the Art Institute of California – Inland Empire. He wanted to visit the observatory in advance to do some sound checks, so on October 11th we took him to the 100-inch dome so I could play some sample tunes. Phil took reference recordings with his digital recorder, and determined that we would need to set up mics in several places and then experiment with mixing down the tracks to get the immersive “first person” experience I was aiming for. He rounded up his colleague Ian Vargo as the lead audio engineer, (who would bring his own recording gear), two AI audio engineering students (Brad Delorenzo and Alex Cho) and four fantastic microphones (on loan from AI) – a Royer R-122V and a Neumann U87 for the direct mics, and a couple of AKG C414XLS-ST (matched pair) for the distance mics. Ian brought his own recording gear, using Universal Audio Apollo as an interface into ProTools. After an evening of rain that had me worried, the recording day – November 2, 2014 - dawned partly cloudy, very cold (in the mid 40s up on the mountain), but with no chance of rain. Nik and I loaded up our respective gear (flutes, camera equipment, food for the crew, bags of skier’s handwarmers), and headed up the Angeles Crest Highway. On the way up, traffic came to a complete stop due to a motorcycle crash on the crest; cars were parked up and down the road in both directions, with many people climbing up nearby ridges to see what had happened. After about 20 minutes we saw the rescue helicopter airlift the victim off the mountain, and we were allowed to pass. I suppose this impacted my state of mind for the evening, and put me into a contemplative mood.

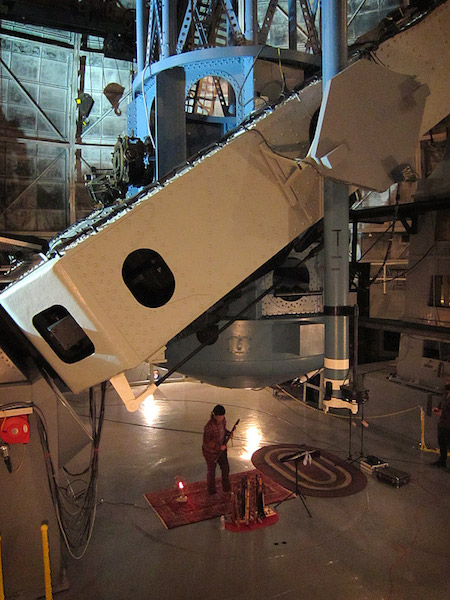

Everyone got to Mount Wilson safely, and we started setting up around 4:30 pm, shortly before the grounds close to the public for the evening. The 100-inch dome, built in 1917, is approximately 95 feet tall and 100 feet in diameter. The telescope, weighing in at 87 tons, was parked in its vertical position and I, being relatively short, could stand right underneath it to play (in the exact spot I had recorded my test track). The main observatory floor (a.k.a.”the bullring”) is accessed by a very long flight of metal stairs, but to save everyone’s energy at that high elevation, we chose to load in all the equipment on the “skiff”, using a heavy-duty crane to lift everything up to the main level. This was the first time I had seen the crane in action, which also involved dome rotation to position the skiff to be lowered down into the bullring. I had no problem trusting my load of flutes, food, camera and video equipment to the skiff, but when it came time for the recording crew’s load-in, we had to repeatedly assure them that it was safe: “That’s how we got Steven Hawking into the observatory, and we didn’t drop him - we’re not going to drop your recording gear, either.” The crew was intrigued to see dome rotation in action, and had the same reaction as any other first-timers – they couldn’t believe the entire building was revolving around the telescope, as the crane swung the skiff up and over onto the observatory floor. The photo shows the original setup, directly under the telescope. You can see the white worklights (instead of the usual red) along the inside of the dome.

Set-up went fairly quickly, considering the hundreds of feet of cable that were needed to place the mics in the desired locations. Although the interior red observing lights had been swapped out with white worklights, it was still relatively dark and we often needed flashlights for detailed work. The air inside the observatory had the familiar smell of a machine shop – cold metal, motor oil and transmission fluid (which I made sure was not going to drip on me during recording). A few straggling tourists were intrigued by all the commotion and stopped to take photos - we politely cleared them out at 5pm, as we converted the Visitor Gallery into an impromptu recording engineering room. Complete with glass windows separating me from the audio engineers, it was like being in an exceptionally large, cold and dark recording studio.

Ken Evans had the foresight to retrieve an old vintage radiant heater from his garage, and set it up near where I would be recording in the bullring (you can see it glowing in some of the photos). This turned out to be the most valuable piece of equipment brought that night – the temperature inside the un-heated dome was in the 40’s and dropping; even with fingerless mittens and hand-warmers, I wouldn’t have been able to play for nearly three hours without some extra heat.

While the recording crew was stringing what seemed to be hundreds of feet of microphone cable, I assembled my flutes, and set up my index card “set list” on a music stand draped with a towel, so I could make production notes as I went along. After a few minutes of sound checking from the Visitor Gallery, Ian came out to check the acoustics, and decided we should move the mics away from the original location under the telescope, because we were getting too much slap-back from the huge concrete piers that support the telescope. We dragged everything about 10 feet away from the center and re-tested all the mic positioning, until we were sure we were getting a clean sound. Gathering the crew for the obligatory pre-live recording talk & mobile phone-check, Nik told the story of the bear who broke into the galley kitchen by ripping out an air conditioner and breaking through the window just to grab a mango that had been left out on the counter. Once we had verified that no one had left any food in their cars, we were ready to get started. In this photo of the recording control room setup in the Visitor Gallery, you can see the entire recording crew (from left to right): Philip Mantione (in headphones); Brad Delorenzo; Ian Vargo (in headphones), and Alex Cho.

After playing first tune of the session (originally called “Realm of the Long-Eyes”), Phil came into the bullring & asked if I wanted to listen back to the first track – at that point I decided I was not going evaluate the takes during the recording, because it would have taken me out of the “flow” of the experience. So, as I worked my way through the set list, we did each tune one time only (no second tries) – partly because I start each improvisation by completely clearing my head, and partly because the cold damp conditions were causing the flutes to wet-out (fill up with moisture and become unplayable) in an astonishingly short time. Between the intense heat of the space heater, the chill of the night-time air temperatures, and the tiny glowing vacuum tube heart of the Royer mic, the whole experience was remarkably like playing by a campfire. We recorded for about 45 minutes with the low flutes, then took our dinner break, moved on to the mid-range flutes, took another short coffee break to warm up, and finished with the high flutes, resulting in nearly 90 minutes of usable music. I was surprised by the fact that some of my favorite flutes did not perform well under the cold, damp, conditions while others that that I like less, or play less often, held out better in those conditions. As we went along we made notes about some extraneous noises - cars driving by, airplanes overhead, a few mysterious thumps and clanks, and the barking of G.W. Richey, the observatory dog (who can be heard on a couple of the tracks). This photo shows me playing “Spirits of the Long-Eyes” from the control room point of view. You can see Alex in front of the computer, with Ian just off-screen to the left.

Because the mics would pick up any sounds in the room (footsteps, or the sound of another person breathing), and the bullring was relatively dark (even with a few white worklights installed), we wound up with relatively little documentary video or photography of the actual recording session. In the next post, I’ll talk about post-production and track selection. Here are audio links for tracks 9 – 12 of the album – enjoy!

9) Spirits of the Long-Eyes (Kitt Peak National Observatory) http://soundcloud.com/user779060191/spirits-of-the-long-eyes

I chose the unique scale of the Anasazi flute to represent the negotiations between the Tohono O’odham people and the team of astronomers appointed by the National Science Foundation who desired to build an observatory on the mountain called “Ioligam”. The eerie whistling in the background (one of the reasons this tracks was ultimately included) is the result of the natural sound of the flute, combined with the accoustical effects of the observatory dome. This was the first tune of the recording session. I was still settling in to the whole situation, felt a little uncomfortable with the setup and was initially dissatisfied with the technical aspects of the piece. Others convinced me that with a little editing, the slightly shortened version the song was worthy of inclusion on the CD. Prayer Rock (Anasazi-style) cedar flute made by Michael Graham Allen (Coyote Oldman), key of low A.

10) Amazing Grace – Trail of Tears http://soundcloud.com/user779060191/amazing-grace-trail-of-tears

This hymn was sung by the Cherokee as they were forced to march from their ancestral lands to a reservation as a result of the Indian Removal Act of 1830. The harshness of the march and cruel conditions led it to be called the Trail of Tears. I chose the double flute to represent opposing forces. I set the 2nd flute’s drone to the song’s tonic (B major) but moved my right hand down to the drone for the improvisation section, in order to create new harmonies by choosing alternative notes. You’ll also hear sum and difference frequencies, which make it sound like a choir of flutes is playing. Listening in headphones, you may also hear the distant barking of the observatory dog, G.W. Richey. Double flute made by Brent Haines (Woodsounds) 6- hole concert style in cedar, key of F# minor.

11) Zuni Sunrise – Extended Version (traditional Zuni song) http://soundcloud.com/user779060191/zuni-sunrise-extended-version

This traditional song, known by many tribes, is one of my favorite traditional tunes. For this recording, I found that the unvarnished cedar performed exceptionally well under cold, damp conditions, resulting in a longer improvisation. I was really surprised at the end of the take, to discover I had been playing for over 8 minutes. Flute made by Michael Graham Allen (Coyote Oldman) 5- hole style in cedar, key of E minor.

12) Lark Who Sang His Song to the Sun Every Morning http://soundcloud.com/user779060191/lark-who-sang-his-song-to-the

I chose a bird-like tune to represent both the Navajo constellation (which has no Greek or European counterpart) and the singing of birds at sunrise. The tune however, is inspired by a mockingbird who sat in a tree outside our bedroom window, and would sing enthusiastically to the streetlights each night starting around midnight. Flute made by Ed Hrebec (Spirit of the Woods) 6- hole concert tuned in claro walnut, key of A minor.

For more background and information, please visit www.kokopelli.la

- What a fascinating and wonderful project! The music sounds so incredible coming from the dome of the 100 inch telescope! Why haven't I seen anything about this on facebook? I think you should be showing this to the world! It's spectacular!

- Joanne, I believe that bear you are talking about is the one who stole my mangoes meant for the CUREA participants' dessert. There were probably six or more mangoes, actually, and they were inside a plastic bag which was inside a cooler. The bear tore out the air conditioner from the window, opened the cooler and escaped with the bag of mangoes. Someone saw him carrying it away! Hahaha...it's true too. There were no mangoes for that dessert that next day!

Comments