- Published: Monday, April 11 2016 21:18

As mentioned in my previous post, in the 1970’s my art had become inspired by scientific information about the nature of the universe which was reflected in my primary mode of expression, which at this time was mostly painting. In 1975, my wife and I moved to Zurich which exposed me to a thriving contemporary art scene. Four years later we moved to the US and, after a year and a half, we decided that Switzerland was the better choice for our circumstances and we returned to Switzerland in 1980.

Signs & Symbols

Back in Switzerland, my “particle” painting style continued to develop and I began to integrate geometric and symbolic elements. I found concepts in physics like “singularity” to be really fascinating and how our planet was influenced by cosmic forces such as “space weather. I exhibited regularly in the dynamic Zurich art scene. Also, at this time I took an interest in and joined several humanitarian organizations that had the goal to end hunger and improve the living conditions in the third world. I donated both my time and my art to these endeavors. As the contemporary art scene flourished in Zurich, I became aware of the work of conceptual artists like Joseph Beuys and Christo who, in their own unique ways, involved the public in their art manifestations. In addition to my painting, I began to explore a more conceptual approach to making art by integrating elements of technology into my works.

Because of my earlier personal experience living next to the space center in Florida, and perhaps due to the reinvigoration of the US space program with the early flights of the US Space Shuttle in the early 1980’s, I began to consider making conceptual artworks designed for the space environment. As art is traditionally a form of communication, I thought that any artwork that could be realized in outer space would be, at the very least due to its novelty – a subject of substantial media attention. I also realized that the communication potential would be enormous for a large scale artwork placed in orbit – especially one that could be experienced by people all over the world.

From my perspective, this possibility also came with a certain responsibility and such artworks would have to impart a universally recognized message that could be understood and appreciated among the diverse cultures of the world and function on a universally shared symbolic level. As the beginning of new millennium was just 16 years into the future, I also reasoned that the people of the world would expect some form of event or celebration that everyone could share. I also reasoned that 16 years would be sufficient lead time to realize such a project. Without having any idea of the technical, financial or political complexities involved, in 1984 I initiated the O.U.R.S. – the Orbiting Universal Ring Satellite project. My idea was to celebrate the new millennium with an sculpture in Earth orbit which would be large enough to create a “circle in the sky” that would be visible to most people on the planet to commemorate humanity’s passing into an exciting new millennium with as a symbol of hope, peace and unity. As the acronym “OURS” also meant “belonging to everyone” in English, I wanted this project to be something that would allow people from around the world to participate in its realization.

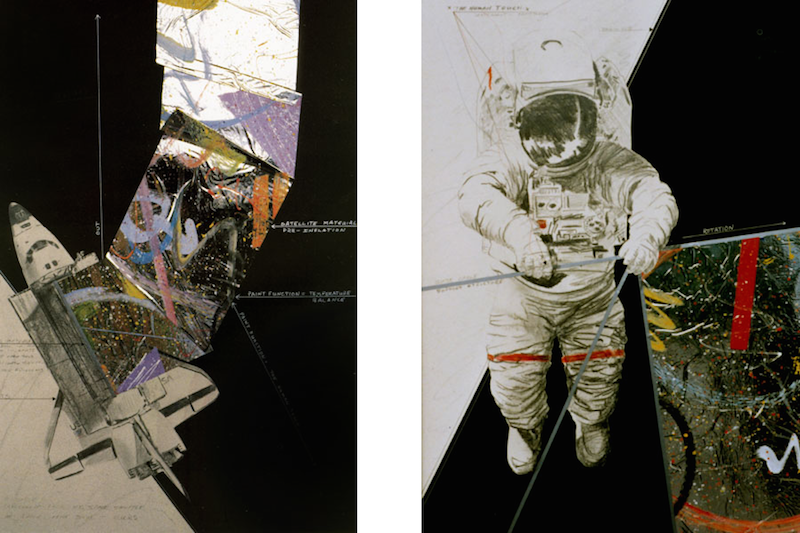

The only engineering intuition that I had at the time was that such a sculpture would need to be constructed out of a very lightweight and highly reflective material. Therefore, I went out and purchased some sheets of Mylar to use as canvas for paintings, project drawings and for exhibition models. As seen in the two early project collages below, I assumed that a big roll of Mylar could be placed in the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle where it could be unrolled in space while some astronauts would assist in the deployment and construction.

Project Drawings, Collage, 1986

Fortunately, I learned about a space event – a trade fair called “Space Commerce” that was scheduled to take place in Switzerland in the summer of 1986. I thought that this would be an opportunity to present my project to the space community and to get some feedback on the technical feasibility of such a project, and I subsequently contacted the organizers. They were actually quite open to the novel idea of including a space art project in the technology exhibition if I was willing to make a professional display and pay the same rate for the exhibition space as did the other exhibitors which included many of the major aerospace companies in the world.

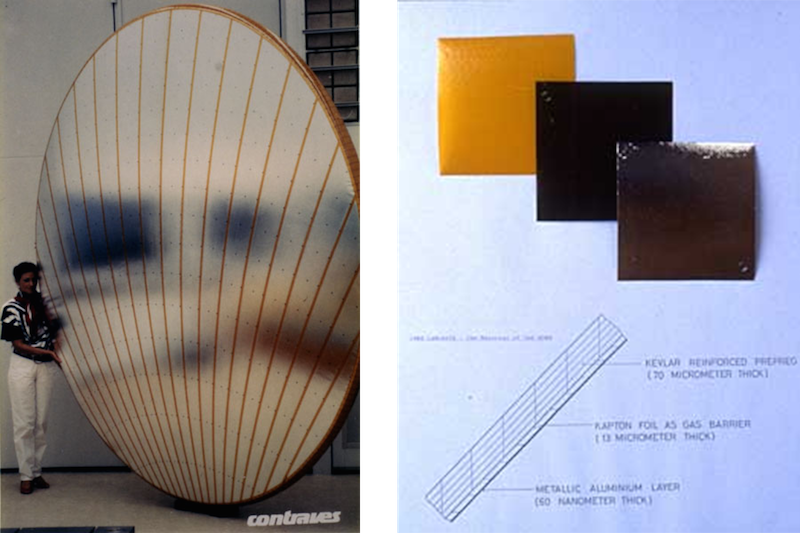

Though the cost to present the O.U.R.S. project in this professional space event was a real challenge for me, it proved to be a real breakthrough. A number of the space engineers I met at the event were receptive and indicated that my project was indeed technically feasible – although not with my roll of Mylar on the Space Shuttle. By coincidence, the exhibitor adjacent to my stand was a Swiss company that was unknown to me at the time called Contraves AG which in fact was located in Zurich only a few kilometers from where I lived. On their stand they were exhibiting an inflatable antenna based on a technology called Inflatable Space-Rigidized Structures (ISRS) that they were developing under contract with the European Space Agency. The ISRS material is a chemically impregnated membrane that would harden - or rigidize - in the presence of sunlight. I immediately appreciated how such a technology could be utilized for the kind of orbital artworks that I was proposing.

Contraves Antenna & ISRS Material

The Contraves staff told me that I was not the first artist to be interested in using their technology and they mentioned a French artist named Pierre Comte that had contacted them earlier about his art-in-space project called ArtSat. They introduced me to Dr. Marco C. Bernasconi who was the engineer leading the ISRS technology development program.

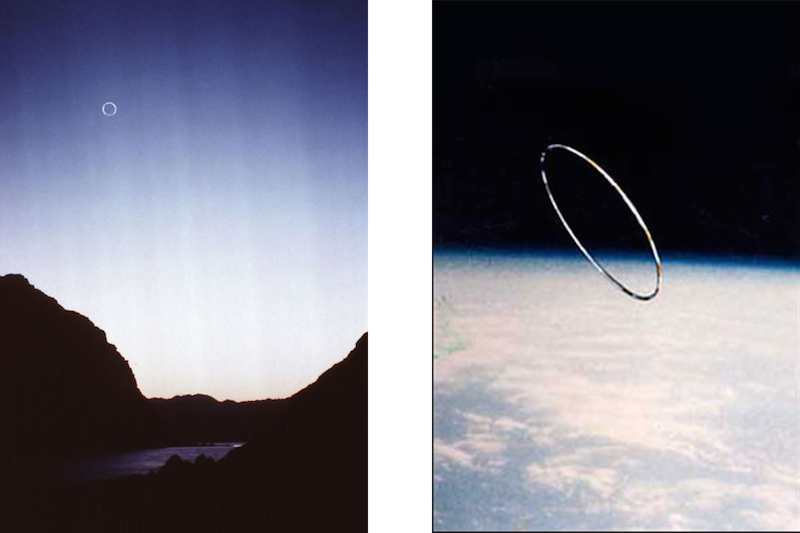

Dr. Bernasconi saw that there was some a potential for synergy between the ISRS technology development and a project such as the O.U.R.S. and with the permission of his company, he agreed to serve as a technical advisor. Over the course of the next few years we were able to come up with a realistic technical definition of the O.U.R.S. based on the ISRS technology which indicated a continuous torus with a diameter of 1 kilometer and a ring thickness of 10 meters. Such an object placed in a 400 km orbit would be visible to viewers on Earth as a "circle in the sky" approximately 1/4 the size of the Moon. With a magnitude of -7.2 the sculpture would be much brighter than the brightest star Sirius which has a magnitude of -1.14, or Jupiter -2.0 or Venus -4.4. Using the ISRS material that was available at that time the sculpture would have an area/mass ratio of 0.2 kg/m2 resulting in a launch mass of 19,740 kg. Such an object would require the total payload capacity of an Ariane 5 or a Titan 4 launcher.

A Circle in the Sky O.U.R.S. 2000

At $200 million for the launch and a perhaps similar amount for building the O.U.R.S., we realized that was much to be done in the coming years to meet the deadline in the year 2000. As with any other technological program we decided to proceed via a step-by-step approach. The idea of building and launching a smaller object to test the concept and the technology was a logical next step.

The O.U.R.S. was not the only orbital art project being proposed during this time. The one receiving the most publicity was the Eiffel Tower’s competition in 1986 to celebrate its 100th anniversary with visible orbital sculpture. The winner of the competition was Group Spirale consisting of: Alain Coquet, Jerome Gerber, Jean Jacques Leonard, Alain Robert, and Jean Pierre Pommereau. Their project was called L’anneau Lumière - a ring with a diameter of 24 kilometers consisting of 100 reflecting balloons, each 6 meters in diameter - which would have been visible as a circle in the sky larger than the Moon. This project stimulated substantial protest from the astronomical community and, as it was probably technically non-feasible, the idea was eventually cancelled by the Eiffel Tower Corporation. Pierre Comte’s ArtSat mentioned earlier, was the second place winner and Dieter Kassing’s Space Disk - a sculpture concept also based on the ISRS technology - placed third. For the 1990 Goodwill Games, American artist James Pridgeon was proposing an orbital sculpture called the Goodwill Constellation which would have connected several inflatable spheres along a tether creating a precise line of lights in the sky. Speaking of synergy, in 1987 Contraves built an ISRS torus with a diameter of 6 meters for development test purposes. As most of the development for this object of this size and shape had already occurred we felt using a similar object would be a suitable and relatively inexpensive prototype for the O.U.R.S. development program.

6 meter ISRS torus, Contraves AG

To differentiate from the larger O.U.R.S. and to make the object more interesting we added a central quadrant and a sphere to the design. This design – a circle divided by a central cross is also the Greek astronomical symbol of the Earth as well as a symbol found in many cultures around the world, such as the medicine wheel in the Native American culture. The central sphere was to contain an archive of the names of the projects supporters and the word “peace” in all languages would be printed on the reflective surface.

We called this precursor project the OUR-Space Peace Sculpture (OUR-SPS) and we set a goal to realize the project in conjunction with the 1992 International Space Year (ISY) as a way to commemorate international cooperation in space. As the size of the OUR-SPS was only 6 meters in diameter and, as such, not large enough to be visible to viewers on Earth, we also wanted to be able to make a film of the deployment and inflation of the sculpture in orbit.

In order to meet these criteria, we assumed that the only way to deliver and film the OUR-SPS deployment would be via the US Space Shuttle. In 1985 information sent to the OURS project by NASA indicated the existence of a “Non-Scientific Payload Program” specifically set up to deal with payloads of a non-scientific nature such as art. We also learned about NASA’s Get Away Special (GAS) program which could accommodate the OUR-SPS. In 1984, artist Joseph McShane’s GAS project S.P.A.C.E. and, in 1986, a project called Vertical Horizons by Ellery Kurtz and Howard Wishnow, were flown under this program.

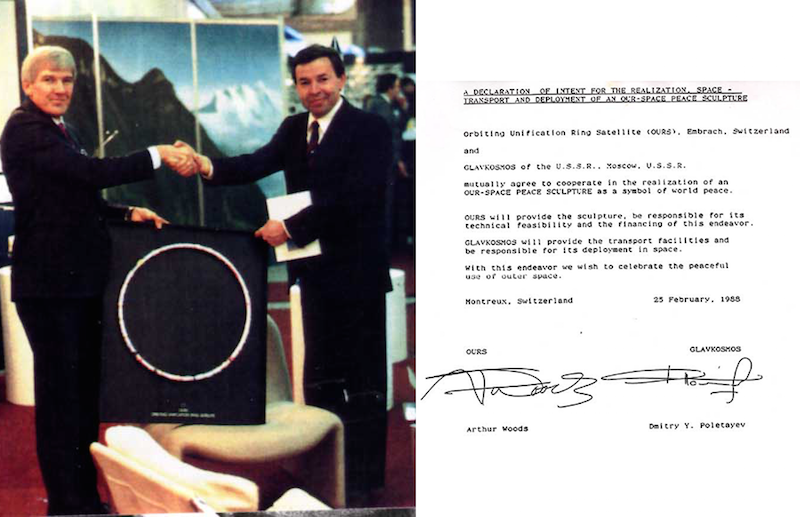

Another flight opportunity appeared in the summer of 1987 when it was announced that the Soviet space program would begin offering its services on a commercial basis through a special agency called Glavkosmos. On January 13, 1988, identical proposals were sent to both NASA and Glavkosmos requesting an offer to transport and deploy the OUR-SPS. From Glavkosmos we learned that they would be open to discuss our project at Space Commerce’88 taking place in Montreux, Switzerland where both they and the OURS project would be exhibiting.

During that event, on February 25, 1988, a “Letter of Intent" was signed between the OURS project, Glavkosmos and its commercial agent V/O Licensintorg to deploy the OUR-SPS from the Mir space station. The text of the agreement read: “OURS and Glavkosmos mutually agree to cooperate in the realization of an OUR-Space Peace Sculpture as a symbol of world peace”.

“Letter of Intent” signed with Glavkosmos

Glavkosmos provided a diagram of the container that would transport and deploy the OUR-SPS from the Mir space station. The maximum dimensions were 32cm in diameter and a length of 51 cm which would enable the payload container to pass through the air lock of the Mir space station. It was agreed that the OURS project would pay the commercial rate of $15,000 per kg they were charging for experiments flown on the Mir. With our payload estimated to weigh approximately 10 kg the total cost of the transport and deployment was set at $150,000.

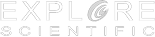

OURS-SPS deployment from the Mir station

Transport container diagram

Technical discussions with Glavkosmos commenced and, as this was in the pre-Internet age, most of our communications were via Telex machines or by normal postal services as even Fax machines were not common in the USSR at that time. The announcement of this agreement resulted in substantial international publicity which gave the project much initial momentum.

Regarding our proposal to NASA, at a meeting at their Washington headquarters on May 31, 1989, I was informed that the GAS-reservation list was frozen due to the backlog resulting from the Challenger disaster, but that existing reservations could be transferred in accordance with established procedure. We were provided with information about the program and a list of existing GAS-reservation owners. In December 1989, a select list of GAS owners received a mailing indicating our interest to purchase their GAS reservation. One respondent to our letter concerning the GAS transfer was the German firm Kayser-Threde GmbH of Munich. They sent a letter informing us that they had managed several successful flights of GAS payloads but they would not sell us a GAS reservation without providing the accompanying services themselves. I contacted Kayser-Threde to ascertain their interest in combining their experience in the GAS program with Contraves’s ISRS technology for the realization of the OUR-SPS. Meetings between all three parties were held in July, 1990.

On 31 July 1990, Kayser-Threde and Contraves issued a joint statement confirming their readiness to assist the realization of OUR-SPS deployment from the shuttle. Kayser-Threde GmbH would serve as prime contractor and handle project management, system engineering and payload infrastructure, as well as serve as the NASA/GAS interface. Contraves AG would be responsible for providing the ISRS object. The OURS Foundation would be responsible for the funding.

During my first visit to Moscow and to the Glavkosmos offices in 1988, I was taken to visit Star City, introduced to local space artists and met with school children. The media package of having an American artist, using European technology on the Soviet Mir space station – Mir is the Russian word for “peace” - seemed to fit nicely with our goal of commemorating the 1992 ISY with an example of international cooperation in space with a message of peace – after all the Cold War was at its peak. However, it seemed like a practical idea to pursue both avenues to launching the OUR-SPS as the Europeans were probably more comfortable using the US space systems.

Public Painting at Art Basel, 1988 A “Piece of the Ring”

Presentations about the project were made at the 40th International Astronautical Congress in 1989, in Torremolinos, Spain and at the 41st congress held in Dresden, Germany. Also, during this period, the project was exhibited at the prestigious international art fair Art Basel in 1987, 1988 and 1989 where both the public and other artists became involved in the project. Exhibitions and presentations were also made in France, Germany, Switzerland, the U.K. and in the USA. Public painting activities were organized at some of these art events where the public was invited to paint on large walls of Mylar. The painted Mylar material was then cut into small squares and sold as “pieces of the ring” – an early example of “crowdfunding”. To add a humanitarian dimension to the project, a percentage of the funds being raised for the OUR-SPS at the events, was donated to the UNICEF Oral Rehydration Therapy (ORT) program.

A project with such political dimensions and which involved the USSR and Swiss space technology did not go unnoticed by the Swiss government. I actually suspected that my phone was being listened to and I later learned, in what was called the Fichenaffäre or “secret files scandal” that, indeed, my meetings with the Soviet space representatives in Switzerland as well as my contacts with the USSR Embassy were being followed and monitored. At the time, no test article of the ISRS technology had been flown in space (although material samples were later launched on the ESA EURECA platform in 1992, and returned to Earth in July 1993), and we assumed that Contraves would welcome such a flight opportunity as an important in-orbit demonstration of the ISRS technology.

Unfortunately, in spite of this opportunity, involvement of other space companies and significant public and sponsor interest, Contraves informed us that it had decided to withdraw its support for the project. It was not clear whether this decision was due to technical reasons or due to political reasons, but the decision was more than disappointing for both me and my technical partner Dr. Bernasconi who was employed there.

We feared that this would complicate our relations with Glavkosmos which had been positively progressing. On a subsequent visit to Moscow in 1989, not wanting to disappoint our Soviet partners, Marco and I tactfully explained the withdrawal of his company’s support from the project and our desire to go forward. To our surprise, we were then introduced to engineers from NPO Energia – the space company responsible for the Mir space station – who showed us a photo of two inflatable 20 meter in diameter tori deployed in space as an antennae experiment on a Progress rocket in 1984. Since Contraves had stepped out of the project, they offered to build, transport and deploy the OUR-SPS from the Mir space station. The deployment would involve the participation of a cosmonaut who would film the deployment and the video would be transmitted to ground stations. A price of 1 million Swiss francs was agreed to.

Two 20m antennas - The deployment of the OUR-SPS from the Mir station

Two 20m antennas - The deployment of the OUR-SPS from the Mir station

NPO Energia was very enthusiastic and, in 1990, they built a full size OUR-SPS which was presented to us at SpaceCommerce’90, again held in Montreux, Switzerland. It was inflated on-site and displayed during the trade fair.

Full size OUR-SPS built by NPO Energia Exhibited at Space Commerce’90, Montreux, Switzerland

Full size OUR-SPS built by NPO Energia Exhibited at Space Commerce’90, Montreux, Switzerland

Due to the growing financial and legal issues associated with the project an organizational structure was obviously needed. Thus, in 1990, with generous help from a major Swiss law firm, I founded the non-profit OURS Foundation – a cultural and astronautical organization. Marco would be the vice-president and my wife and a close friend agreed to serve on the board of directors.

From the statutes:

The primary purpose of the OURS Foundation is to introduce, nurture and expand a cultural dimension to humanity's astronautical endeavors. This task will be manifested through the identification, investigation, support and realization of related cultural, astronautical, humanitarian, environmental and educational activities which may take place both on and off planet Earth, and which are deemed as beneficial to the development and advancement of human civilization in this new environment.

A Swiss marketing specialist became very interested in the project who then engaged the German public relations firm ABC/Eurocom to create a global communications and fundraising strategy. Meetings with potential sponsors took place. With these ongoing activities, developments, and with the full cooperation of the Soviet space organizations using their own space technology, everyone involved was confident about the eventual realization of the OUR-SPS in 1992.

Then, in 1991 the Cold War unexpectedly ended and, in December that year, the USSR officially dissolved. Due to the uncertainties associated with pursuing the project within this new political context, sponsor support for the 1992 ISY opportunity was withdrawn and the OUR-SPS project was postponed which, in turn, impacted the development program for the realization of the O.U.R.S. intended for the year 2000 which was also postponed. In my next post I will discuss the two art projects that were realized on the Mir space station in 1993 and 1995, and other cultural activities.

Comments