by Nicole Gugliucci

- Published: Wednesday, April 10 2013 07:00

Many of us have an experience with astronomy that involves looking up at the night sky with our own eyes or putting an eye to a telescope. Whether it is seeing the Milky Way for the first time from a dark site, gazing at Magellanic Clouds, or seeing Saturns rings, we all want to share that experience with as many people as possible so that they can have it, too. I like to go one step further and share the invisible universe with anyone who cares to see it.

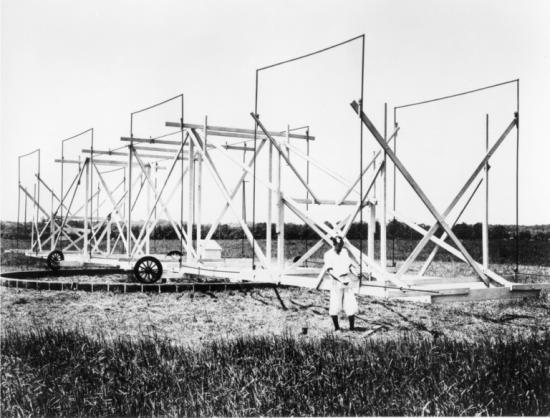

Drawing of William Herschel’s experiment. image courtesy: Wikipedia

One can say that the first experiment in “invisible astronomy” occurred in 1800 when William Herschel held a thermometer beyond the red end of the spectrum when he passed sunlight through a prism. The thermometer rose unexpectedly, leading him to conclude that some kind of energy existed beyond the red. However, infrared astronomy did not take off as a science until the 1960s. The break in optical-only astronomy would come from another, unexpected source.

By the 1930s, radio had become a popular technology and was explored for uses in entertainment and communication. An engineer by the name of Karl Jansky was tasked by his employer, Bell Labs, to determine the reason for static around 20 MHz for transatlantic radio communications. Jansky built a large antenna in Holmdel, New Jersey, and used it to identify three sources of static: nearby lightning, distant lightning, and a third signal that he could not yet identify but that rose and set everyday. However, it didn’t have a period of 24 hours, but rather 23 hours and 56 minutes. With a basic knowledge of astronomy, he realized that the source of the static was astronomical and probably coming from the center of the Milky Way. A New York Times headline in 1933 announced, “New Radio Waves Traced to the Centre of the Milky Way,” but the story never caught interest in astronomical circles and Jansky eventually moved on to other projects.

Karl Jansky’s set up in Holmdel, NJ. (Image courtesy of NRAO/AUI)

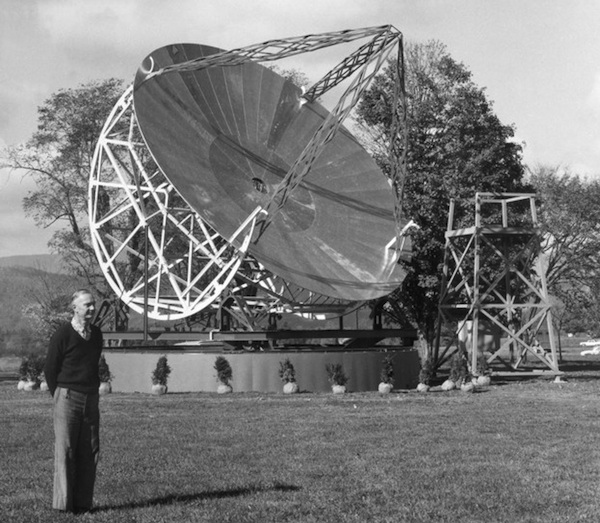

However, a bright and eccentric young engineer by the name of Grote Reber picked up on the story and decided to try his hand at building a radio telescope specifically to study what Jansky found. He eventually built a 31-foot diameter radio dish in a field owned by his family in Wheaton, Illinois, and spent all of his spare time looking for the radio signal from the sky. He confirmed Jansky’s discovery and made the first maps of the emission from the Milky Way. He submitted his results to the Astronomical Journal, but frankly, they didn’t know what to do with them. In his words, years later, Reber recalled, “The astronomers of the time didn't know anything about radio or electronics, and the radio engineers didn't know anything about astronomy. They thought the whole affair was at best a mistake, and at worst a hoax.” However, after several visits to his homemade facility by astronomers, the editor of the journal agreed to publish his findings. And it’s a good thing, too. Reber’s work laid the foundation for an exciting period of exploration that followed World War II using decommissioned military radars around the world.

Grote Reber and his telescopes at its restoration in Green Bank, West Virginia. (Image courtesy of NRAO/AUI)

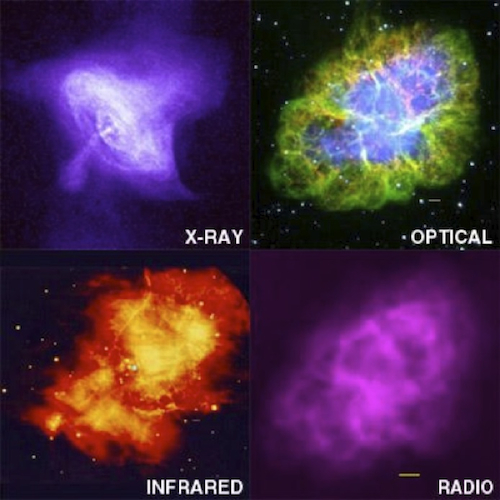

Today, radio astronomy is a sophisticated study of the Universe, as are the fields of infrared, ultraviolet, x-ray, and gamma-ray astronomy. Even though we can’t see the Universe in this way with our eyes, it is thrilling to share the images of pulsars, supernova remnants, galaxies, and superluminal jets with the technology we have at our disposal. But radio astronomy is still accessible to the layperson, as the Society of Amateur Radio Astronomers can tell you. You can build a radio telescope to detect the invisible light coming from the Sun, Jupiter, meteor showers, or molecules in interstellar gas clouds. Although I’ve done research with world-class radio telescopes, I am still collecting old satellite dishes in my garage with the intent of building up some Itty Bitty Radio Telescopes of my own.

The Crab Nebula and pulsar as seen in different parts of the electromagnetic spectrum. (Credits: X-ray - NASA/CXC/SAO, Optical - Palomar Obs., Infrared - 2MASS/UMass/IPAC- Caltech/NASA/NSF, Radio - NRAO/AUI/NSF)

I take inspiration from the story of Grote Reber, a curious and driven person who identified with the “maker” culture decades before it became a movement. He is my favorite citizen scientist for just getting out there and exploring where no one had before. So don’t forget to look around you and imagine your environment as you can’t quite see it, and appreciate the invisible universe as well as what you can see with your eyes.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Infrared_astronomy

http://www.nrao.edu/whatisra/hist_jansky.shtml

http://www.lsst.org/radio/jansky.shtml

http://www.nrao.edu/whatisra/hist_reber.shtml

http://aas.org/obituaries/grote-reber-1911-2002

###

Dr. Nicole Gugliucci is a postdoctoral astronomer and educator with CosmoQuest. Now at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, she did her PhD in astronomy at the University of Virginia and the National Radio Astronomy Observatory and hugs just about every radio telescope she can find.

Dr. Nicole Gugliucci is a postdoctoral astronomer and educator with CosmoQuest. Now at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, she did her PhD in astronomy at the University of Virginia and the National Radio Astronomy Observatory and hugs just about every radio telescope she can find.

Comments