GAM 2018 Blog

- Published: Saturday, April 21 2018 09:00

By Rick Fienberg

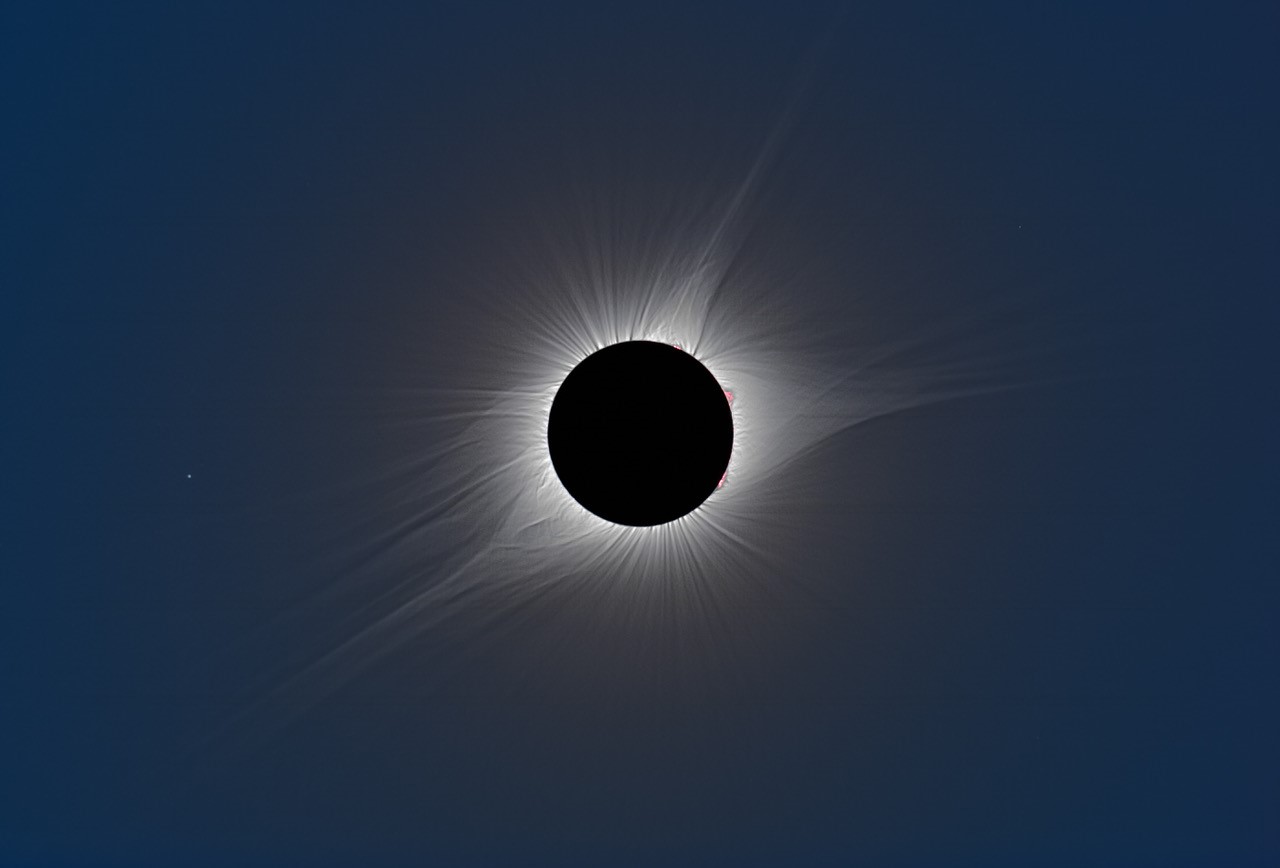

The total phase of the August 21, 2017, solar eclipse as seen from Madras, Oregon. This is a composite of short, medium, and long exposures, as no single exposure can capture the huge range of brightness exhibited by the solar corona. Credit: Rick Fienberg & TravelQuest International, with processing by Sean Walker of Sky & Telescope.

It’s been eight months since the “Great American Eclipse,” the first total solar eclipse to touch the U.S. mainland since 1979 and the first to stretch from coast to coast in nearly a century. I hope you were among the tens of millions — including me — who thrilled at the sight of the pearly white solar corona framing the jet-black lunar silhouette in a cerulean sky. Or perhaps you were one of the hundreds of millions who stood outside the narrow path of the Moon’s dark shadow and had only a partial eclipse. Either way, if you saw the Moon block the Sun last August 21st, you won’t soon forget the experience.

I won’t, though there are times I wish I could. The eclipse itself, which I watched from central Oregon, was one of the prettiest I’ve seen. But in the weeks leading up to the event I went through hell, and it was the eclipse’s fault.

Here’s what happened. I work for the American Astronomical Society (AAS), the major U.S.-based organization of professional astronomers. With the eclipse still years away, we created a task force to promote awareness of the event, to disseminate instructions for safe viewing, and to facilitate widespread distribution of solar-viewing glasses and filters. Our aim was to avoid a problem we’d seen in other countries at previous eclipses, where astronomers encouraged people to observe the Sun with proper precautions but doctors warned people to stay inside to avoid any risk of eye injury.

The AAS and NASA jointly developed safety messaging that won the endorsement of three major societies of professional ophthalmologists and optometrists. We based our advice on the ISO 12312-2 international safety standard for solar viewers, which was adopted in 2015, well in advance of what was predicted to be the most-observed solar eclipse in history. Our basic message was simple: Except during totality, look at the Sun only through viewers that are certified to meet the ISO 12312-2 standard. Among the AAS task-force members, I was the one principally responsible for promoting this message, which I did though our website (eclipse.aas.org) and through press releases, social-media posts, and media interviews.

So far, so good. But about a month before the eclipse, the marketplace was flooded with counterfeit eclipse glasses and solar viewers, most of them apparently imported from China and sold on Amazon.com. They claimed to meet the ISO 12312-2 standard, but there was no evidence backing that up, whereas vendors of legitimate products posted documentation from accredited testing labs. By the time Amazon started to properly vet their sellers, the damage was done: the public was confused about whether any solar filters were truly safe.

By this point I should have been packing my bags for Oregon and testing my automated eclipse-photography setup. Instead I was fielding a barrage of phone calls and emails from journalists and eclipse-event organizers desperate to make sense of the situation. I frantically compiled an online list of manufacturers and dealers selling genuinely ISO-compliant solar viewers and issued a press release about it. In the days leading up to August 21st, that web page got millions of hits, orders of magnitude more than the AAS has ever seen on any of its websites!

Fortunately, we’ve seen very few reports of eye injuries from the eclipse. On the plus side, this probably means that very few truly unsafe solar filters made it into people’s hands. On the minus side, it probably means that after hearing about the problems with eclipse glasses sold on Amazon.com, many people opted not to watch the eclipse at all out of concern that their solar viewers might be unsafe.

As it turned out, I managed to get my best eclipse photos ever last August 21st, even though I had to scramble at the last minute to get my gear in order. And I’ve been appointed to a committee charged with revising the ISO 12312-2 safety standard to make it more bulletproof against counterfeiters, so I’ll be able to make something good out of my miserable experience.

I have wonderful memories of my eclipse expedition to Oregon, and I look forward to the next major solar eclipses coming to the U.S. — an annular in October 2023 and a total in April 2024. Those aren’t so far away, but with any luck, by the time they get here I’ll have forgotten how crazy things got in August 2017!

|

Rick Fienberg is Press Officer of the American Astronomical Society, former Editor in Chief of Sky & Telescope magazine, and a veteran of 13 total solar eclipses.

|

|