GAM 2018 Blog

- Published: Wednesday, April 25 2018 09:00

By Ricardo Reis

No, that’s not a mistake. The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is turning 28 years old this month. Think about it. That’s a whole generation of people that never knew a world without a space telescope! They were born, grew up, graduated, some might have already married and had children – I’d even bet that some are actually working with Hubble data right now! And that’s the current lifespan of the most recognizable (and one of the most prolific) telescope in the world.

And the most amazing thing? For a telescope that started being planned in the 1960’s, and launched on the 24th of April 1990, it’s still able to produce cutting edge science, and of course, breathtaking images that look like real life paintings.

Why am I writing about Hubble? Because keeping up with tradition, HST just released new anniversary images. This time the target was a part of the Lagoon Nebulae, in visible and infrared, and the images don’t disappoint.

Visible (left) and infrared (right) images of a 4 light-years across part of the Lagoon Nebula. Some of the stars revealed in the IR image are young stars formed within the nebula. Credit: NASA, ESA, STScI

Three years ago, when the Porto Planetarium had just reopened after going digital, I was tasked to produce a fulldome planetarium show to celebrate Hubble’s 25th anniversary. It should feature a few of the most iconic Hubble images, so I immediately thought about past anniversary images.

But I soon realized that these wouldn’t be enough to showcase the richness of Hubble’s legacy. It observed the Solar System, Nebulae and Galaxies of all shapes and sizes, protoplanetary disks, exoplanets, galactic mergers, galaxy clusters with dark matter acting as a lens that shows even more distant galaxies, and of course, the Hubble Deep Fields.

You cannot talk about Hubble’s “greatest hits” without mentioning the deep fields. They are windows to the evolution of our Universe, looking further and further back to more than 13 billion years in the past, when our Universe was just a few hundred thousand years old.

The original Deep Field was produced in 1995, and revealed about 3000 galaxies. The latest was the Ultra Deep Field, originally produced in 2004, but revisited three times: Infrared data was added in 2009; a smaller portion dubbed the Extreme Deep Field added a further 5500 galaxies in 2012; Ultraviolet data, which shows the hottest, largest and youngest stars, was added in 2014.

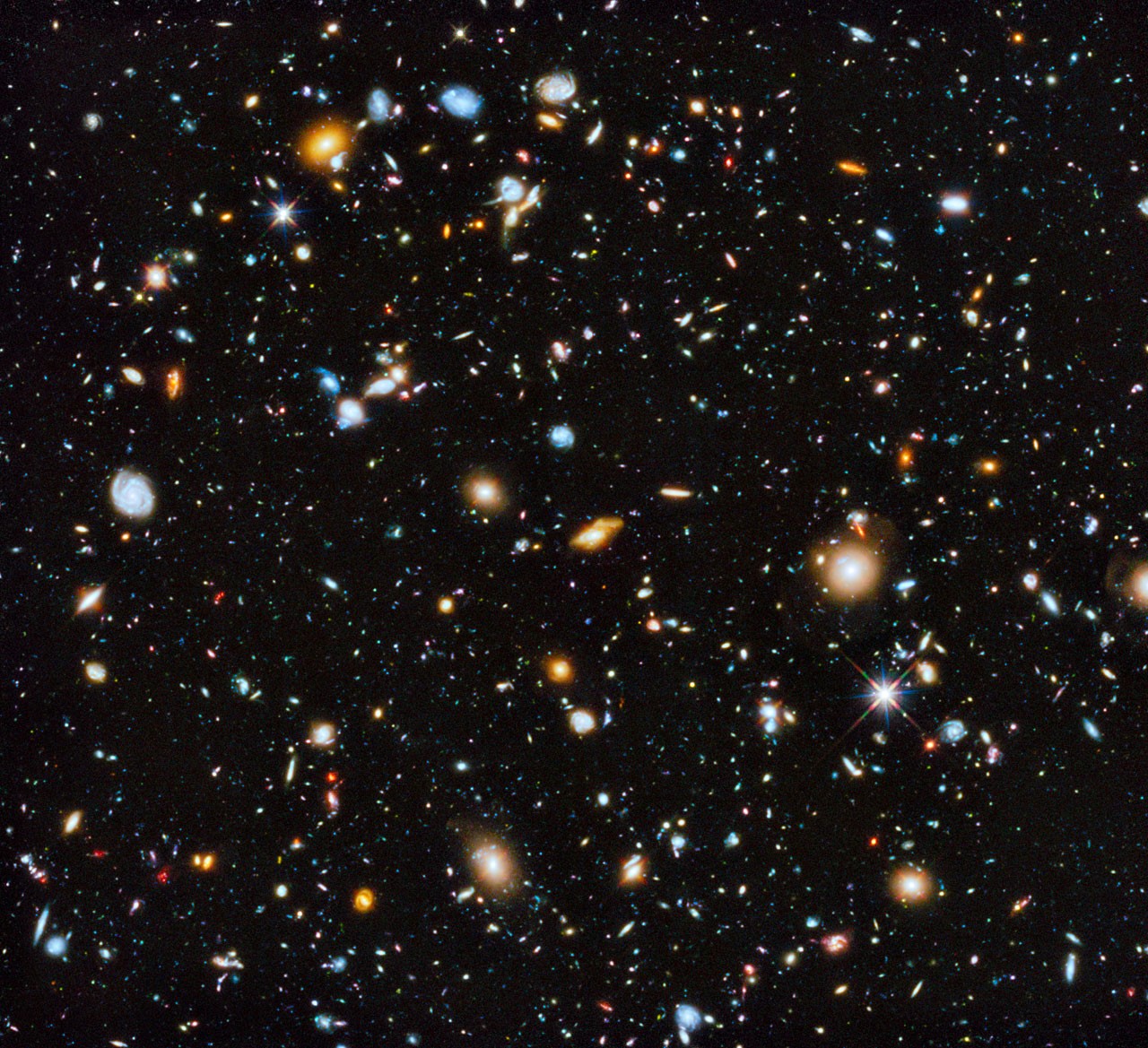

The composite image below of infrared, visible and ultraviolet data was constructed over the course of 841 orbits, spanning 10 years, which summed up 25 days of observations. It contains over 10 thousand observed galaxies, including candidates to the furthest galaxy ever observed.

Ultraviolet Coverage of the Hubble Ultra Deep Field (UVUDF) project. Credit: NASA, ESA, H. Teplitz & M. Rafelski (IPAC/Caltech), A. Koekemoer (STScI), R. Windhorst (Arizona State U.) & Z. Levay (STScI)

However, the days of this joint NASA/ESA project are numbered. It’s already way past its original life expectancy, but it’s still holding on, waiting for its successor, the (recently delayed again) James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

The JWST was originally planned to be launched in 2007, but its successive delays forced one last overhaul of Hubble in May of 2009. As of last month, JWST was again delayed, and is now planned to be launched in May 2020.

In 2021, at 31 years old, Hubble is expected to stop its science work. After that, the most likely scenario is that NASA will let it slowly fall towards the Earth, and when it’s too low, send a small rocket to couple with the decaying telescope, to crash safely in the middle of the ocean.

Hubble orbiting the Earth. The picture was taken by astronauts on board the space shuttle Columbia after the Servicing Mission 3B. Credit: NASA/ESA

|

Ricardo Cardoso Reis works as science outreach officer at Instituto de Astrofísica e Ciências do Espaço (IA) and as planetarium producer/presenter at Planetário do Porto – Centro Ciência Viva, in Portugal. Between 2010 and 2012 he was solar activities coordinator for Global Astronomy Month. During the International Year of Astronomy 2009 (IYA2009) he was a member of the International task group and Portuguese co-coordinator for 100 Hours of Astronomy (and co-coordinator of “Sun Day” activity) and Galilean Nights; and the International coordinator of Dawn of IYA2009, the first global event of IYA2009.

|

|