The search for change on the moon – a search in vain

People have often fancied that the moon was an active world, even harboring life. Many observers, both professional and amateur, have believed that they stumbled onto visual evidence suggesting changes occurring on the moon, perhaps from vulcanism, perhaps due to life.

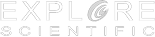

1. Between the craters Walther and Gauricus. Best seen: April 25 and 26 in the evening sky; and April 6 and 7 in the morning.

1671. Several times, Giovanni Domenico Cassini thought he saw a misty formation, perhaps a cloud.

2. Gassendi, crater. Best seen: April 9 and 10 in the morning sky; and April 27 and 28 in the evening.

1776. English astronomer William Herschel imagined that the shading variations on the crater floor were caused by the changing shadows of a vast forest of trees that were several times taller than those on Earth.

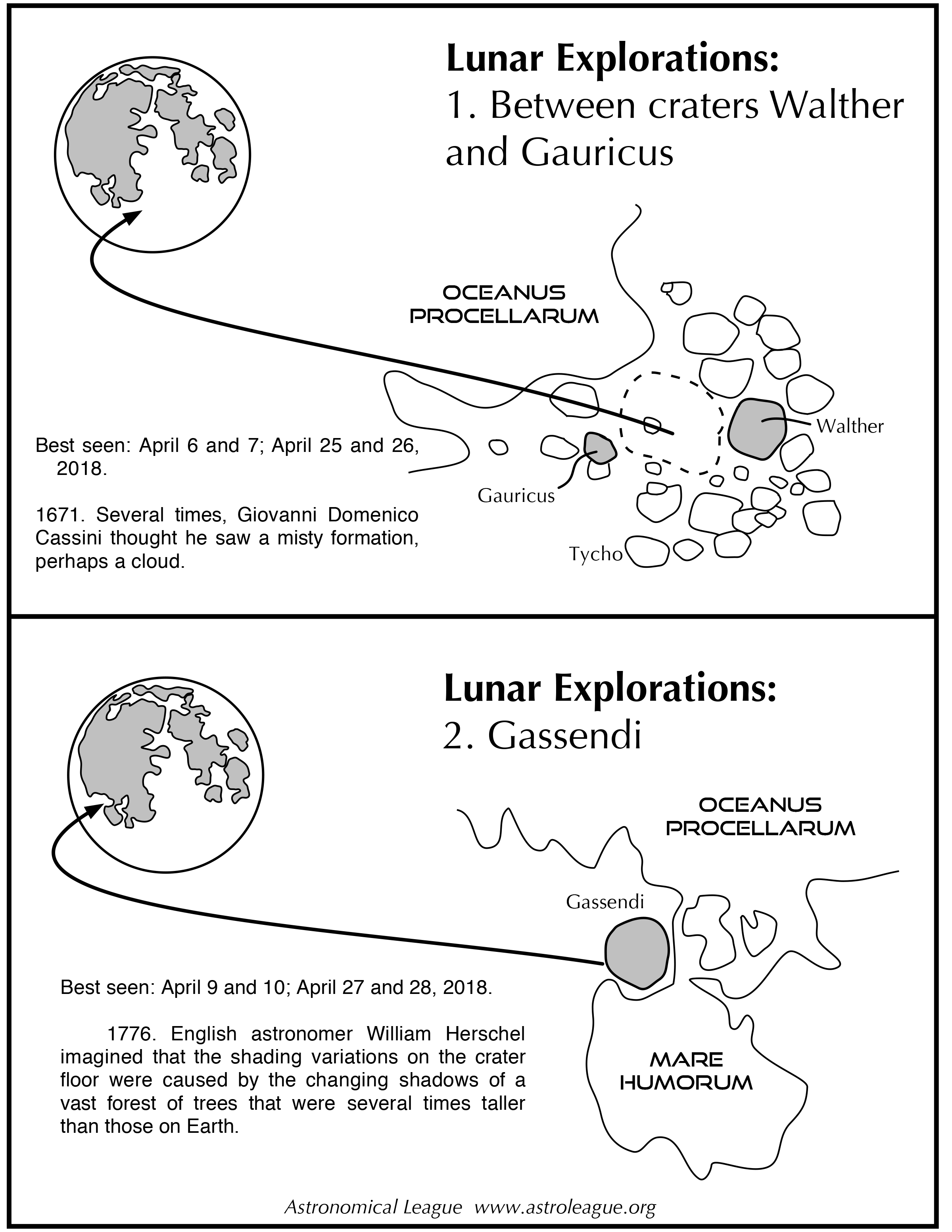

3. Hevelius, crater. Best seen: April 11 and 12 in the morning sky; and April 29 and 30 in the evening.

1787. German observer Johann Hieronymous Schroeter suspected that a volcano recently formed in the Hevelius crater.

4. Alhazen, crater. Best seen: April 17, 18, and 29 in the evening sky.

1791. Schroeter saw changes in the definition of the crater that he thought were possibly due to mist or vegetation.

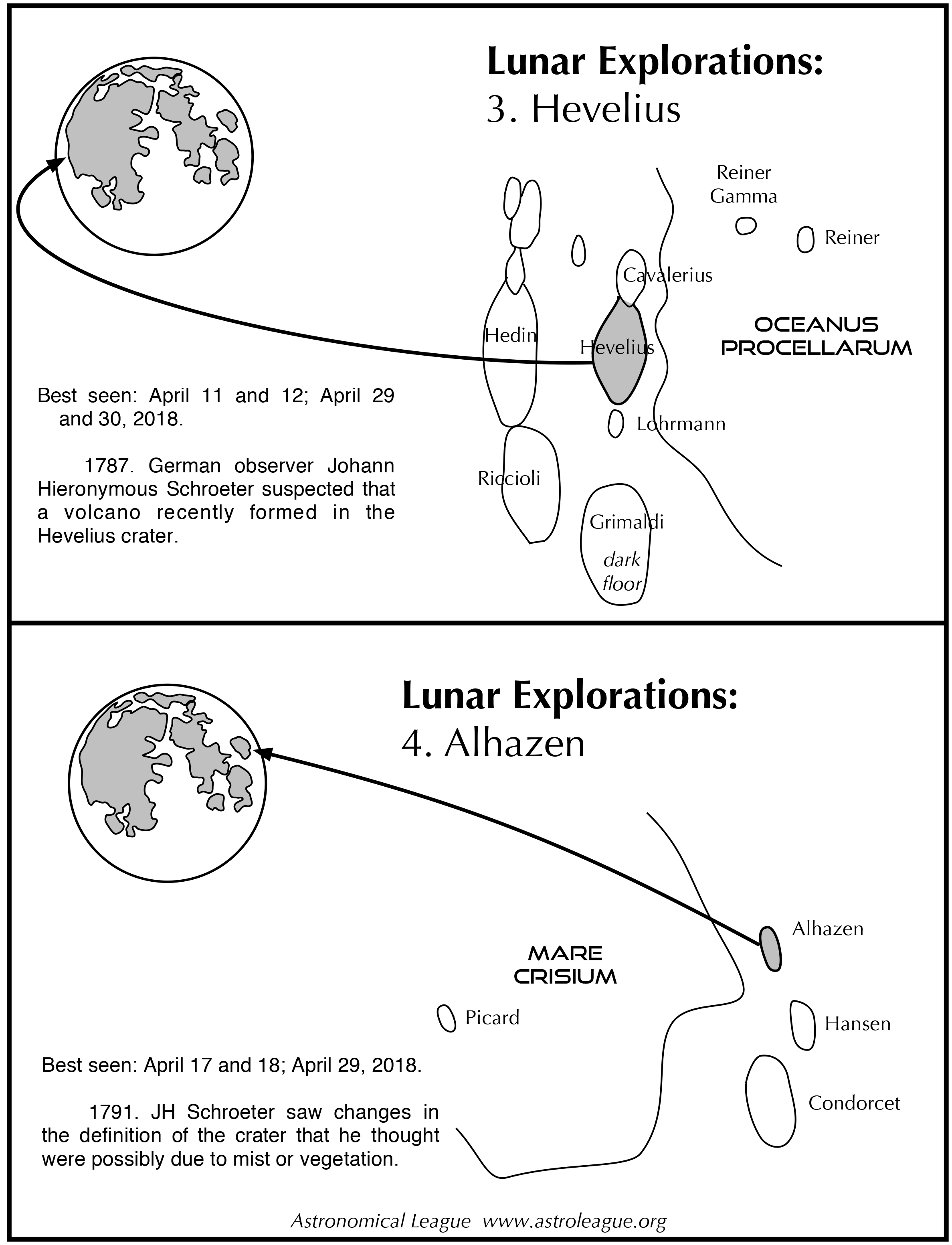

5. Two-thirds of the distance from Eratosthenes to Schroeter in Sinus Aestruum. Best seen: April 24 and 25 in the evening sky; and April 6 and 7 in the morning.

1822. Bavarian observer Franz von Paula Gruithusien saw the layout of a great lunar city, Wallwerk.

6. Sinus Iridum. Best seen: April 7 and 8 in the morning sky; and April 26 and 27 in the evening.

1837. During the Great Moon Hoax, newspaper writer Richard Adams Locke reported that rational beings were said to live there.

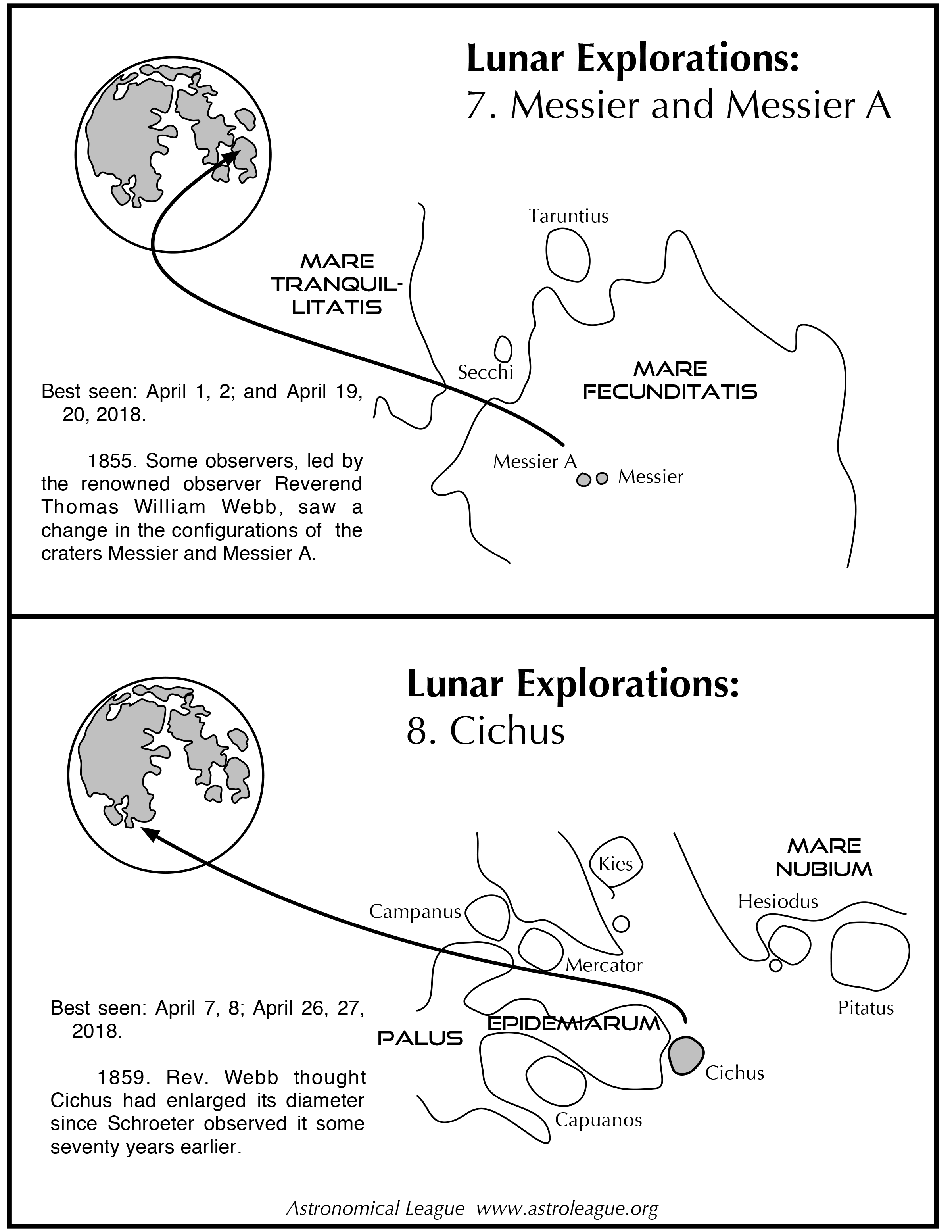

7. Messier and Messier A, craters. Best seen: April 1, 2, 19, and 20 in the evening sky.

1855. Some observers, led by the renowned observer the Reverend Thomas William Webb, saw a change in their respective configurations.

8. Cichus, crater in Mare Nubium. Best seen: April 26 and 27 in the evening sky; and April 7 and 8 in the morning.

1859. Rev. Webb thought it had enlarged its diameter since Schroeter observed it seventy years earlier.

9. Fracastorius, crater. Best seen: April 2 and 3 in the morning sky; and April 21 and 22 in the evening.

Circa 1870. French astronomer Jean Chacornac. Fragmentary walls believed to have formed from oceanic erosion.

10. Plato, crater. Best seen: April 25 and 26 in the evening sky; and April 4 and 5 in the morning.

1869. English amateur astronomer William Radcliffe Birt encouraged his colleagues to closely examine the flat floor of Plato for any signs of change.

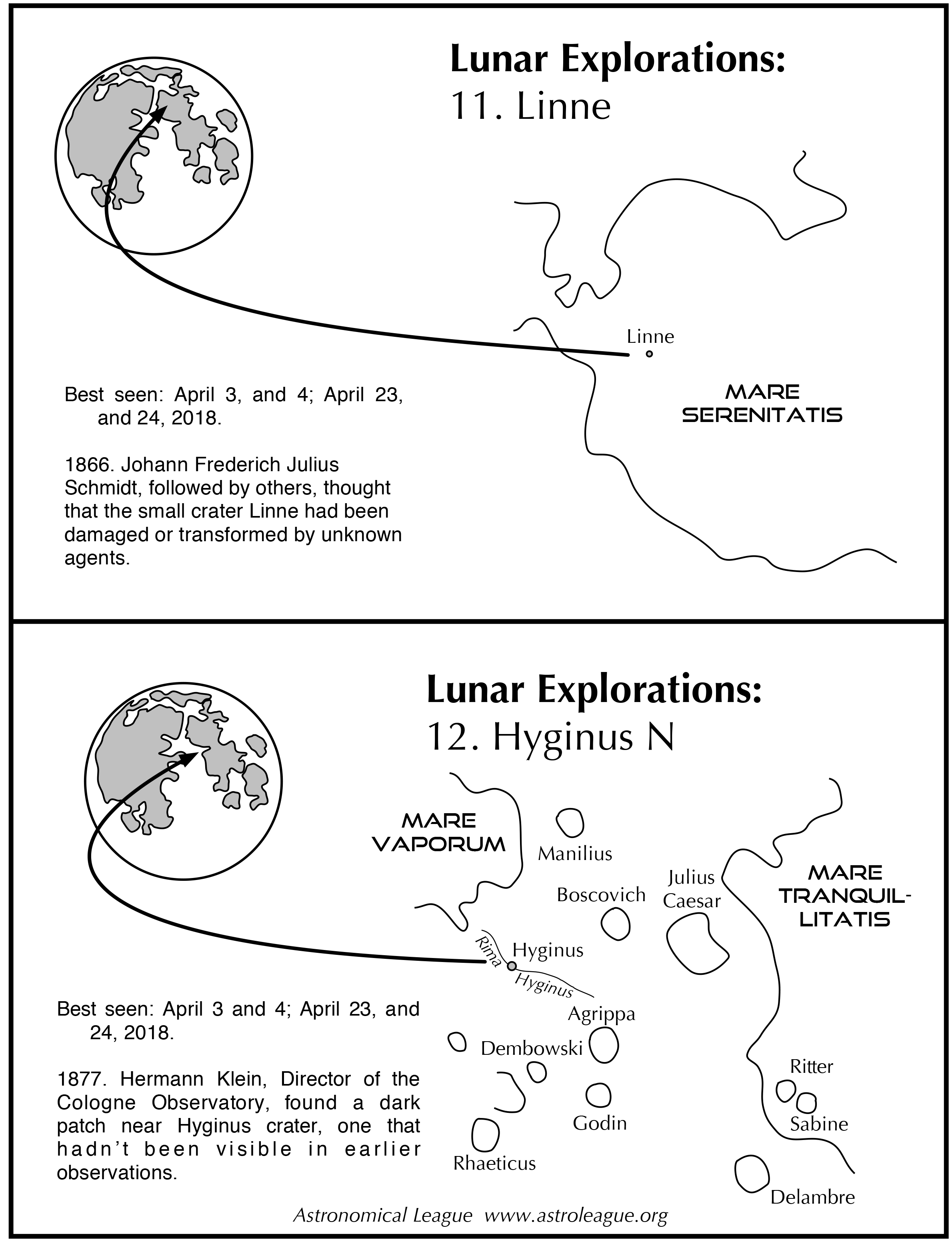

11. Linne, small crater. Best seen: April 23 and 24 in the evening sky; and April 3 and 4 in the morning.

1866. Johann Frederich Julius Schmidt, followed by others, thought that crater Linne had been damaged or transformed.

12. Hyginus N, near crater Hyginus along Rima Hyginus. Best seen: April 23 and 24 in the evening sky; and April 3 and 4 in the morning.

1877. Hermann Klein, Director of the Cologne Observatory, found a dark patch near Hyginus crater, one that hadn’t been visible in earlier observations.

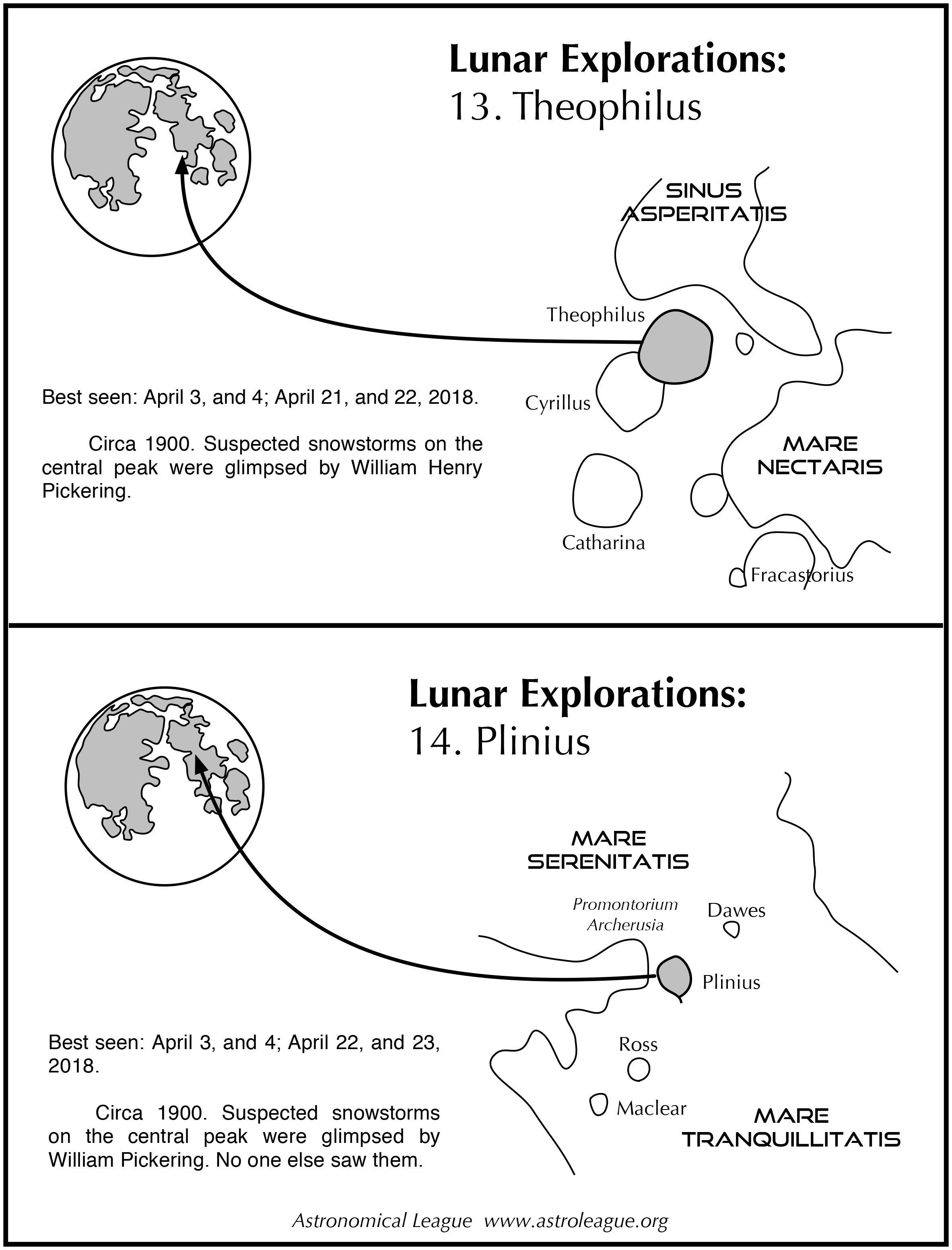

13. Theophilus, crater. Best seen: April 21 and 22 in the evening sky; and April 3 and 4 in the morning.

Circa 1900. Suspected snowstorms on the central peak were glimpsed by William Henry Pickering.

14. Plinius, crater. Best seen: April 22 and 23 in the evening sky; and April 3 and 4 in the morning.

Circa 1900. Suspected snowstorms on the central peak were glimpsed by William Pickering.

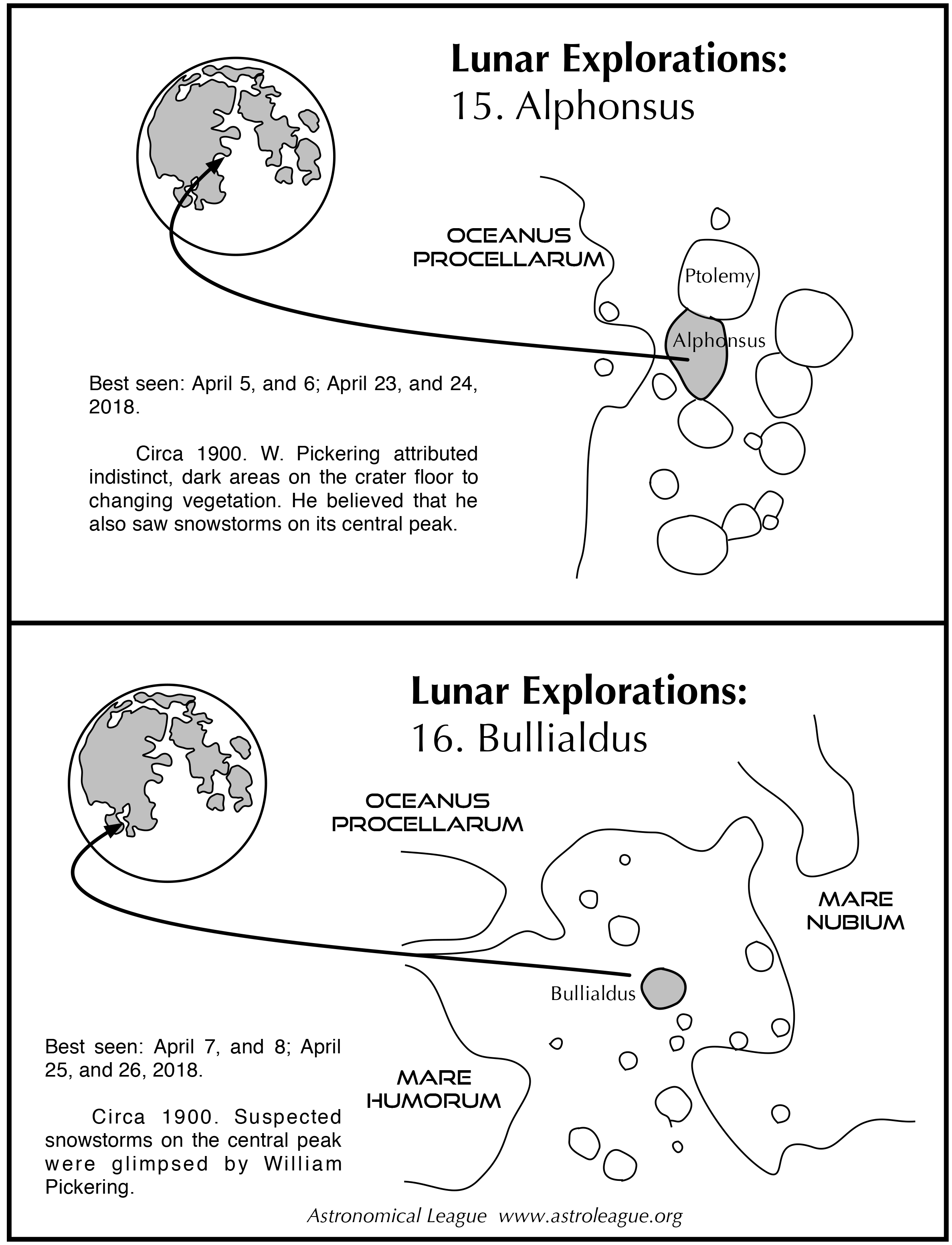

15. Alphonsus, crater. Best seen: April 23 and 24 in the evening sky; and April 5 and 6 in the morning sky.

Circa 1900. Pickering attributed indistinct, dark areas on the crater floor to changing vegetation. He believed that he also saw snowstorms on its central peak.

16. Bullialdus, crater. Best seen: April 25 and 26 in the evening sky; and April 7 and 8 in the morning.

Circa 1900. Suspected snowstorms on the central peak were glimpsed by William Pickering.

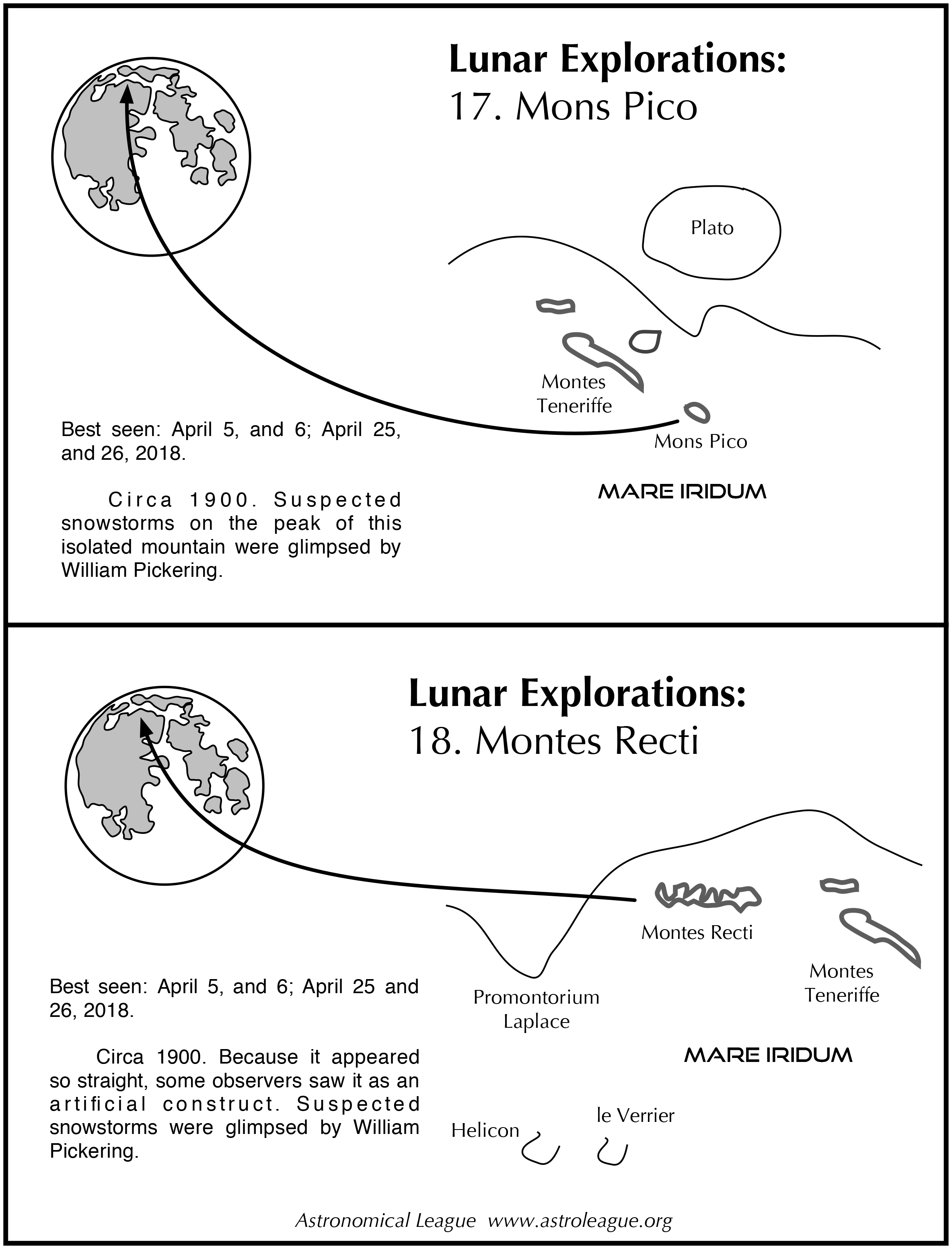

17. Mons Pico, lone mountain. Best seen: April 25 and 26 in the evening sky; and April 5 and 6 in the morning.

Circa 1900. Suspected snowstorms on the peak of this isolated mountain were glimpsed by William Pickering.

18. Montes Recti, straight mountain range. Best seen: April 25 and 26 in the evening sky; and April 5 and 6 in the morning.

Circa 1900. Some observers saw it as an artificial construct. Suspected snowstorms were glimpsed by William Pickering.

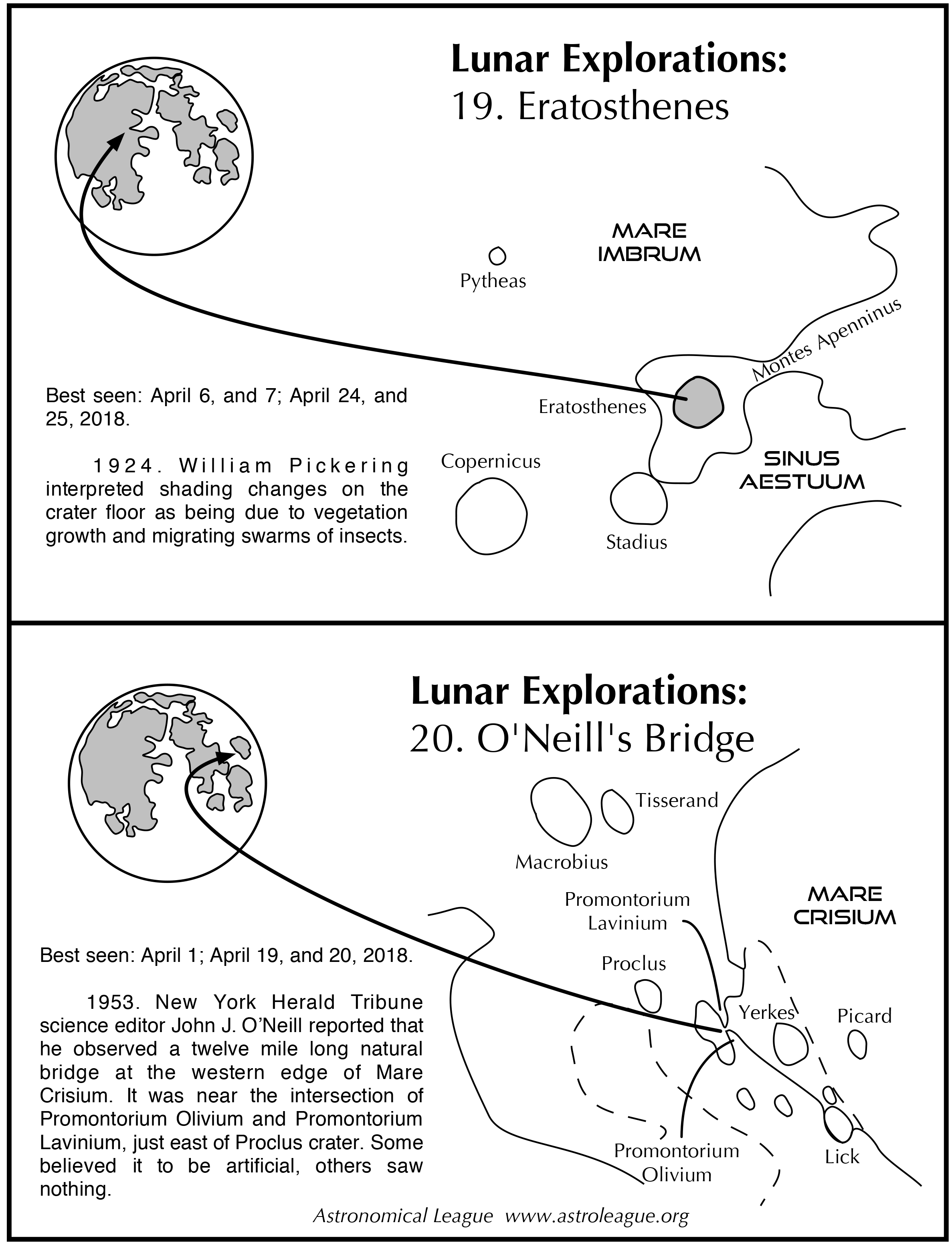

19. Eratosthenes, crater. Best seen: April 24 and 25 in the evening sky; and April 5 and 6 in the morning sky.

1924. William Pickering interpreted shading changes on the crater floor as being due to vegetation growth and migrating swarms of insects.

20. O’Neill’s Bridge, mistaken formation. Best seen: April 1, 19, and 20 in the evening sky..

1953. New York Herald Tribune science editor John J. O’Neill reported that he observed a twelve mile long natural bridge at the edge of Mare Crisium near the intersection of Promontorium Olivium and Promontrium Lavinium, just east of Proclus crater. Some believed it to be artificial, others saw nothing.

**********************************************************

Resources:

Moore, Patrick, Guide to the Moon, 1953, Eyre and Spottiswoode Publishers

Webb, Rv. TW, 1962, Celestial Objects for Common Telescopes, 6th revision, Dover

Sheehan, William; Dobbins, Thomas, 2001, Epic Moon, Willman Bell

Wood, Charles A., The Modern Moon, 2003, Sky Publishing

Rukl, Antonin, Field Map of the Moon, 2005, Sky Publishing

Birren, Peter, Objects in the Heavens, 2011, Birren Design