Report

- Published: Monday, June 17 2013 15:50

AWB AstroArts Project chair, Daniela De Paulis in a conversation with Jon Ramer, President of the International Association of Astronomical Artists (IAAA).

How did you get interested in Space Art? What was your first encounter with it?

My interest in space came about as a child when my father was stationed in Florida and I got to see some of the Apollo moon launches in person. I remember the awe at the whole world shaking from the sound of a Saturn V booster going up. I thought rockets were pretty cool before that, but afterwards I was obsessed! I quickly discovered Star Trek and science fiction by Asimov, Clarke, Heinlein, Haldeman, Aldriss, and others and my imagination never came back down to Earth. My childhood was filled with drawing rockets, moon landers, and alien ships with lasers blasting; I even built entire fleets of spaceships out of Legos and fought giant space battles. Eventually I joined the US Air Force (like my father) as an officer because the Air Force dealt with space more than any other service. Shortly after coming on active duty, I was walking through a bookstore and saw a book on the shelf titled “The Grand Tour” by Ron Miller and William K. Hartmann. The instant I opened the cover I was hooked. The book was filled with image after image of incredible sights from around the solar system, places where humankind had not yet been, up close and personal. I was so inspired by the artistry in the book that I immediately read it cover to cover, then went out and bought my first paints, brushes, and canvases. Through that book I discovered that Bill and Ron were members of an organization dedicated to painting space art, The International Association of Astronomical Artists (IAAA). I quickly located the IAAA and joined myself. I’ve been a lifetime member for more than 20 years now and am more than pleased to say that Bill and Ron are friends and that I’ve had the chance to personally thank Bill for his inspiration. What made the thank you even more special is that Bill and I were on the side of a volcano painting a view of the caldera at the time! We were attending one of the IAAA’s special events, an artist’s workshop. Every couple years IAAA artists gather at some exotic location on Earth where the local natural scenery is analogous to features on other planets to get ideas on what could be “out there” and make sure what we depict is both accurate as well as inspirational. We’ve been to Death Valley, the Badlands of Utah, Yellowstone, the Grand Canyon, Meteor Crater, and the volcanoes of Iceland, Tenerife, Washington and Hawaii, plus many other locations – and more to follow in the future. One of the best things about our workshops, besides seeing neat places with like-minded artists, is the chance to collaborate with those artists and produce a group painting of some otherworldly setting.

Utah Strip Painting by Several Members of the IAAA

Your first post focuses on the origin of this field and touches upon its links to the history of geographical explorations. The role of the contemporary Space artist could be compared to that of the artist/explorer who used to make drawings of maps and natural phenomena during the age of geographical explorations. Do you think someday in the future, artists will be able to join Space missions?

Absolutely, yes, in fact, it has already happened. Not only was cosmonaut Alexi Leonov an accomplished artist before going into space, but so was Apollo 12 Moonwalker Alan Bean (who is also a Fellow member of the IAAA). Additionally, space tourist Guy Laliberté is an artist and even took paints into orbit on his visit to the ISS and painted while there. Additionally, NASA at one time had an Artist-in-Space program similar to the Teacher-in-Space program. I’m sure that program will come back someday. IAAA member Dan Durda is in training right now for multiple flights on Virgin Galactic and XCOR within the next two years. I can’t wait to see what art he creates out of those experiences. Many members of the IAAA compare what we do to the Hudson River School of naturalist artists such as Albert Beirstadt, Thomas Cole, and Frederick Church. In the late 1800’s these artists painted amazing works depicting the natural beauty of the American landscapes. Many American citizens did not believe the written reports of the explorers who went out to discover what the new parts of the country held, they thought the descriptions of vast canyons, towering mountains, winding rivers, and massive waterfalls were exaggerations. Then the artists went out and painted what they saw. The exhibitions showing giant canvases of incredible vistas were like the blockbuster movies of today. People flocked to see them, and by doing so created a demand in the population to go and expand into that land like we have today. We in the IAAA feel it is our mission to do the same, inspire the population to demand humanity move off our planet and out into space.

What would their contribution be, in the age of digital photography and media?

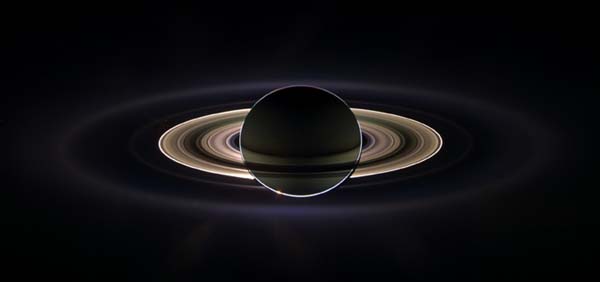

An artist can depict things that a digital camera simply cannot. A charge couple device (CCD) circuit in a camera may be able to capture a wider range of photon wavelengths than the human eye, but it still takes a human to imagine what those photons mean and how they will impact a viewer. Humans add the element of emotion to art. The perfect example of this is a photograph of Saturn taken by the Cassini Imaging Team. This marvelous panoramic view was created by combining a total of 165 images taken by the Cassini wide-angle camera over nearly three hours while the spacecraft drifted in the darkness of Saturn’s shadow. The head of the imaging team, Carolyn Porco (a member of the IAAA), argued long and hard to take the images, insisting that the artistic value of the image would be worth the effort to create it, no matter how much the science team insisted it was a waste of instrument time. As it turns out, she was right, this picture has become the most popular photo of Saturn ever taken, inspiring the public in ways that mere scientific measurement never could. She argued for the final image based on what it could look like without any way of knowing what it would look like - except in her imagination. That’s what an artist offers that a camera cannot. A camera cannot paint an abstract image or an impression of what the subject matter is about. The photographs taken by Alan Bean while on the surface of the Moon show an amazing landscape in stark shades of gray, but his paintings are filled with color and feeling and are even more amazing than his photos.

Cassini Imaging Team

How do Space Artists position themselves in relation to the art market and the big art institutions?

This is actually a very important topic to me as President of the IAAA. Though the idea of Space or Astronomical Art is deeply engrained in the public consciousness as evidenced by the popularity of science fiction entertainment, the “fine art” market doesn’t yet seem to share that sentiment. Many IAAA artists have experienced the difficulty of getting a gallery to look at our work as anything more than “illustration.” I’ve attended and curated numerous Space Art exhibitions and quite often I am asked, “Where did this photograph come from?” When I answer, “It’s not a photo, it’s a painting,” the response is almost always astonishment. It simply doesn’t occur to most people – including gallery managers – that fine art could be an astronomical landscape image. The idea of living and being in space is popular to the public, but only at some point in the future. Most people think that such a possibility is out of their personal reach in their lifetime and so tend not to focus on artistic expression of something they believe they cannot achieve, hence they prefer art that reflects the images they think they can see and/or achieve, beaches, mountains, the Amalfi Coast, deserts, etc. Galleries are businesses, they exist to sell art, and if few people are exposed to Space Art and fewer still are inspired enough to purchase it, then the galleries tend not to carry it as regular items. The only Space Art gallery I am aware of is NovaSpace out of Tucson, Arizona, run by IAAA Fellow member Kim Poor. The representation of Space Art in major galleries or museums is complicated by a lack of accepted definition of what Astronomical Art is. Some artist’s attempts to add to the genre’s definition to include their personal artistic style only blurs its acceptance. Viewing a work of art in space does not make the work Space Art, nor does creating an image with space age technology, or even making it in free fall. A painting of flowers in a meadow done in zero gravity is not Space Art just because of where it was made, it’s still a landscape piece. The astronomical subject matter and method of expression of that subject is what defines the genre of the work. Art does not need an explanation from the artist to the viewer to tell the viewer what type of art it is. These issues tend to make Space Art more difficult to place in major galleries and institutions. But this will change with time. Fortunately, there are many facets to the genre of Space Art and I’d like to take a moment to briefly describe some of them.

Descriptive Realism: The direct inheritor of the artistic standards of Chesley Bonestell, Descriptive Realism is an aspect of Space or Astronomical Art whose primary emphasis is to show a viewer a scientifically accurate visual depiction of alien places in the Cosmos. Works by artists like Michael Carroll, Mark Garlick, and David A. Hardy are excellent examples of this sub-genre.

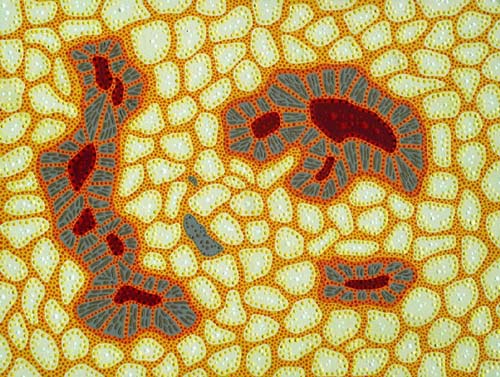

Cosmic Impressionism: Like works done in the impressionist era, Space Art works in the Cosmic Impressionism style use color and form to give a viewer the artist’s impression of the image subject matter without trying to be technically accurate, highly detailed, or adhering to known scientific principles. Despite being more loose, the subject matter is still clearly inspired by space. My preferred style is impressionistic, as it is for Greg Prichett and Kara Szathmary.

Sunspots by Jon Ramer. © Jon Ramer

Sunspots by Jon Ramer. © Jon Ramer

Hardware Art: Hardware Art is usually similar to Descriptive Realism but focusses on the detailed depiction of the hardware of spaceships, probes, and equipment being used in a space setting. Aldo Spadoni, Pat Rawlings, and the late Robert McCall are masters at Hardware Art.

CEV In Low Earth Orbit by Aldo Spadoni. © Aldo Spadoni

CEV In Low Earth Orbit by Aldo Spadoni. © Aldo Spadoni

Sculpture: Works of Space Art Sculpture are more difficult to recognize as such as they are usually more symbolic or abstract in nature, like a rocket shape, stained glass windows representing stellar objects, or a sculptured work designed specifically for zero gravity display. However, the prime inspiration for three dimensional works of Space Art is the same as other styles, space itself. Joy Day and BE Johnson are two superb 3D space artists, as is Arthur Woods, creator of the sculpture “Cosmic Dancer” which was displayed in orbit on the MIR station.

Cosmic Zoology: Though the question of other life in the universe has yet to be answered, artists can speculate about it and imagine the possibilities. Cosmic Zoology is the depiction of extraterrestrial life in extraterrestrial settings. Pamela Lee, Joel Hagen, and Walt Myers create excellent examples of this type of art.

Other Endeavors: Works in other methods of artistic expression such as music composition and dance can also be inspired by space and are considered Space Art in their fields.

How do you envision the future of Space Art?

The future of humanity is in space, so is the future of art. The popular artistic genres of today reflect the popular desires and awareness of humanity at large. A hundred years ago the public focus was on sea and nature art as humans expanded into all corners of our world. As we leave our world and move out into the solar system and beyond, the human need for artistic expression will naturally reflect what we are seeing. When we colonize Mars, images of Mars will become popular, when we move out to Jupiter and Saturn, art works depicting the incredible sights there will become popular too. Someday, a human artist will set up an easel on the rim of a canyon with twin moons and a different colored star in the sky and create a breathtaking landscape painting that won’t even have our Sun as a dot in the sky. And it will be regarded as a true masterpiece by those who view it. That is the future of Space Art.

Where can our readers learn more about Space Art and its different fields?

Check out the IAAA website at www.iaaa.org. You’ll find light years of inspiration there!

Cosmic Chasm by Dan Durda. © Dan Durda

Cosmic Chasm by Dan Durda. © Dan Durda

###

Comments