Discovering the Solar System: Projects for the Keen–Eyed and Camera–Toting Observer (Observing Challenges)

Frances Azaren

Frances AzarenDuring Global Astronomy Month (GAM), AWB shares a series of observing challenges, developed by John Goss and The Astronomical League for astronomy novices to seasoned pro's. Some of these challenges can be completed in a night while others encourage participation for the full month.

Sidewalk astronomers and astronomy club members are invited to create events and engage the public using any of the observing challenges. Please register your event here.

Share your photos from this challenge with us and the world on Facebook, or Tweet using #GAM2019 hashtag and follow (@awb_org).

The “Big Moon” Illusion

A naked eye and camera activity

Casual sky watchers since the time of the ancient Greeks have seen the rising moon appear much larger after it has climbed higher in the sky. The moon is often portrayed in film and television as being very large and bright when it is near the horizon. All this flies in the face of the fact. The actual size of the moon, whether it is rising or it is at its highest point in the sky is quite small. Extend your arm and outstretch your hand. The moon’s apparent diameter is only about 1/4 the width of your index finger.

The common explanation of the “Big Moon” illusion is when the moon’s apparent size is compared to familiar landscape objects, such as distant houses and trees, our mind interprets the moon as being quite large. Then, when it moves higher in the sky, there are no nearby comparison objects. The moon’s apparent size then appears to shrink and it seems to lie much farther away. While sounding plausible, this reasoning does not explain why the same effect occurs at the beach when the moon is seen hovering just above a flat, featureless ocean horizon, or in the desert when the moon is cast against sweeping sand formations. Studies have sought a deeper psychological explanation.

See the big moon illusion for yourself on the evening of April 19th or 20th. From a location that has a low horizon line, look to the east at sunset for the rising moon or on the following morning, to the west at sunrise.

1. Isolate the moon by viewing it through a narrow tube, such as a drinking straw. Note its size compared to the tube’s field of view. Wait two hours or more and repeat the observation. (If it is a morning observation, look a couple of hours before sunrise.)

2. Use a digital camera at full optical zoom and take an image of the rising moon. Be sure the camera is properly focused and that the image is not overexposed. Again, wait a couple of hours, then take another image. Download both images on a computer and view them at the same image scale.

Are the moon sizes the same?

Compare the Size Difference Between Moon at Apogee and Perigee

A camera activity

A direct comparison between the apparent sizes of the moon when it is near perigee (the moon’s closest point to Earth) and when it reaches apogee (the moon’s farthest point) can be made. Perigee occurs on April 16 when the moon is in a waxing gibbous phase. Simply take a digital photo of the moon on either the 15th, 16th, or 17th, shortly before sunrise. Take another image on the night of apogee, March 31, or the night before or after. It also reaches apogee on April 28, so try then, or on the 27th or 29th. Use the camera’s full optical zoom feature and make sure the lens is properly focused. (Try using a manual focus set on infinity.) Be careful not to overexpose the images.

Directly compare the apogee and perigee moon sizes on a computer using the same image scale. The March 31 (or April 28) image will be found to be about 10% smaller than either the April 16 image.

Discover Lunar Libration, Seeing the Far Side of the Moon

A binocular and camera activity

One interesting consequence of the moon’s elliptical orbit is the phenomenon known as libration. The moon presents the same hemisphere towards Earth as it orbits our planet. Therefore, we always see its same side; we never see its far side. Strangely though, during each month, we are able to observe about 59% of the lunar surface.

The moon traces an elliptical path around Earth. One of the features of a body moving in an elliptical orbit is that, when it is nearer to the parent body, it moves faster, and when it is farther, it moves slower. Therefore, the moon moves slowest at apogee and fastest at perigee. All the while, the moon rotates at a constant rate, completing one full rotation every lunar orbit. As a result of these two factors – the changing speed of the moon in its orbital path and its constant rotational rate — plus the changing curvature of its elliptical path, observers on Earth are able at times, to see slightly around the western limb of the moon and at other times, to see slightly around the eastern limb. This is an east-west libration.

There is also a north-south component because, at times, the moon is either slightly above or below the ecliptic, permitting observers on Earth to see slightly over the moon’s south or north polar regions, respectively.

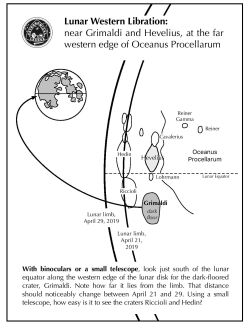

Activity for binoculars or small telescope

Observe the crater Grimaldi near the moon’s western edge. It has a dark floor, making for easy identification. Photograph it using a digital camera at full optical zoom. Be sure to focus the camera and be careful not to overexpose the image. Do this on April 21, or 22 – a few days after full moon – and do so again on April 29 or 30 when it is a thin crescent in the morning sky. Download the images on a computer displaying the same image scale. Closely examine the amount of lunar surface between the western edge to Grimaldi. The April 21 image should show less distance than the April 29 image.

The Moon Plows Through the Hyades

A naked eye and camera activity

From April 9, 9:00 UT to 13:00 UT, the crescent moon moves in front of the northern portion of the Hyades star cluster.

Observe the event through binoculars and capture it with a digital camera. Note the time for each photo. As the minutes pass, the dark edge of the moon slowly moves in front of different stars, blocking them from view. Other stars pop out the moon’s brightly lit crescent side. This demonstrates that even though the moon appears to move westward in our sky, it also travels eastward in its orbit around our planet. It moves about one of its diameters every hour.

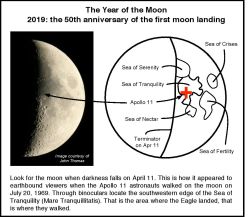

The Year of the Moon:

2019 the 50th Anniversary of the First Moon Landing.

A naked eye, and binocular or small telescope activity

Look for the moon when darkness falls on April 11. This is how it appeared to earthbound viewers when the Apollo 11 astronauts first walked on the moon on July 20, 1969. Through binoculars, locate the southwestern edge of the Sea of Tranquility (Mare Tranquillitatis). That is the area where the Eagle landed and that is where they walked. (Tip: If the moon is too bright, wear sunglasses.)

Activity for binoculars or small telescope

Carefully examine the southwestern edge of the Sea of Tranquility. Can you see the vast flat plain bumping against mountains and craters along the edge?

Sunrise and Sunset Locations

A naked eye activity

It surprises many people the sun doesn’t rise or set at the same location on the eastern and western horizons throughout the year. Earth’s rotational axis is tilted, resulting in the sun rising the farthest south on Dec. 21 and the farthest north six months later on June 21.

On one of the first days of April, note where the sun peeks above the eastern horizon and where it sets along the western horizon. Repeat the observations from the same location on a day at the end of the month. (Do not look at the sun! When it first begins to rise, stopping looking. After its last rays disappear below the western horizon, make your observation.)